The Big Picture…

Which is more valuable – that Ferrari or that Ford truck?

Traditional goods-dominant logic would tell us it is most likely the Ferrari. After all, it will cost more.

But if we use our service-dominant logic lens, then we see value as both i) a measure of how much progress we think we are going to be able to make with an offering, ii) how much progress we have made during and after using the offering.

And since that progress is slightly different each time, and my progress is unlikely to be exactly the same as yours, then those determinations are unique.

Similarly, I bring a different lived experience to this instance of making progress than you. And I will likely

Let’s say our progress is transporting some hardware across town. Now the Ferrari has close to no value.

“Phenomenologically” what a word!

The traditional view of value is where we see value as being embedded and determined by a manufacturer. And measured by the price that customers are willing to pay.

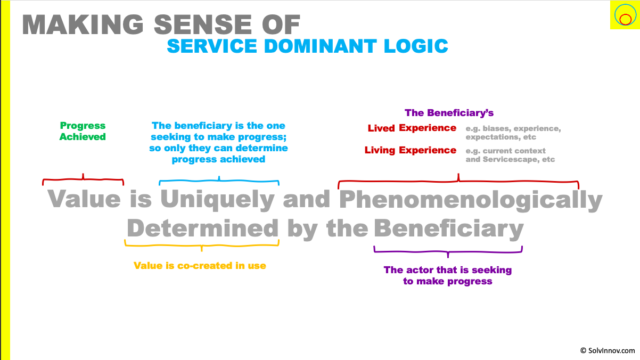

But we know in service-dominant logic we see value as co-created in use. And as such, I have an evolved definition of value. Where value comprises of proposed and achieved value. Both relating to helping a beneficiary make progress (functional and/or non-functional) with some aspect of their life.

As it is the beneficiary seeking to make progress, then it is sensible that they are the only ones that can determine value. Since achieved value equates to how much progress they feel they have made.

And that determination is unique to individual beneficiaries. But is complicated by it being experiential. A beneficiary brings biases, past experience, expectations etc to the service. We will call that their lived experience. They also have an experience during the instance of service they engage in – a living experience. Both of these affect their view of achieved value.

The word phenomenologically is used in the definition of the premise to capture this lived and living experience. So we could re-write this foundational premise as the more approachable:

Value is always uniquely determined by the individual beneficiary based on their lived and living experiences

Implications

This highlights we need our service to be beneficiary centric. We have to understand

- what progress -functional and non-functional -beneficiaries are trying to make

- what generic lived experiences can we leverage or address

- how do we design our service to give the best living experience

And it suggests we need an element of customisation before service starts, and a means of adjusting course during the act of service. If we don’t understand this, then we risk value co-destruction.

The idea

The old school view of value is that manufacturers determine it. And that view is captured in the price. In the background, a marketing team has determined and tested if the customer is willing to pay to own that value. And there is a value-in-exchange moment – the sale.

But in service-dominant logic, we take a different view. We see value as being co-created during the service progression. And actually, it may be co-destroyed as well.

Foundational premise #10 of Service-Dominant Logic states:

Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

Lush & Vargo (2016) – Foundational Premise #10

The idea here is simple: a manufacturer or service provider cannot determine value of a service (and remember that goods, to us, are distribution mechanisms for service). It is the entity that benefits from the service that makes that determination. And they do so uniquely and phenomenologically. What a word!

Let’s break this premise down, and tackle that odd word! We’ll start with refreshing our memory on both who the beneficiary is and what is value.

Who is the beneficiary?

Vargo & Lush (2004) defined service as:

Service is the application of specialised competencies for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself

Vargo & Lush (2004)

Which we can quickly rearrange to give a definition of beneficiary:

The beneficiary of a service is the entity that benefits from the application of another entity’s, or its own, specialised competencies.

Perhaps we should say potentially benefits. Since we know not all service is always successful.

And there could be multiple beneficiaries. Netflix’s main beneficiaries are those people that use the service. But Netflix also benefits – it collects usage data used to steer its future content. And, actually, other customers benefit from the same data leveraged through Netflix’s recommendation engine. Which “reduce the amount of time and frustration to find something great content to watch”.

This is still a little vague though. As we haven’t got a grasp on what “benefits” means. That we will get in the next section. But as a sneak preview, let me write:

The beneficiary of a service is the entity that achieves making progress in some aspect of their life with the application of another entity’s, or its own, specialised competencies.

And with that, let’s take a deeper look at what “benefits” means.

What is value?

Let’s quickly recap my view of what is value.

An enterprise can only create and offer a value proposition. In Figure 1, I call that the proposed value. And it is the offer from an enterprise on how it could help a beneficiary make progress in some aspect of their life. Where that progress can be functional as well as non-functional.

Fundamentally, it is the beneficiary that is seeking to make some progress in their life. So their first step is to determine how well a value proposition will help them. And they potentially have many value propositions to choose between – including do nothing. Subsequently, as the service progresses value is co-created. And the beneficiary will continuously be evaluating that. We, therefore, see value as:

Value is a measure of how well a product has enabled the Beneficiary to make the progress they are seeking

And that measurement can only be one by the beneficiary. It is they that measure and chose a value proposition. And it is they who determine how much progress they have made with the help of the proposition.

Value is uniquely determined by the beneficiary

But, value propositions are, by necessity, generic. They need to attract a sufficient number of beneficiaries to ensure the survivability of the enterprise.

However, it is less likely that a generic value proposition matches the exact progress an individual beneficiary is trying to make. So we need to tighten up “value is determined by the beneficiary” to:

Value is always uniquely determined by the beneficiary

An implication of this is that the value proposition needs to be generic enough to attract sufficient beneficiaries. And customisable to narrow down to the progress individual beneficiaries are seeking to make.

That’s not to say all service has to be customisable. Where progress being sought has little investment on behalf of the beneficiary, customisation may be overkill. Typically commodities and basic needs services drift into this territory. But we can’t say commodities and basic needs don’t need customisation; nor that more complex service must have customisation. And that’s because the beneficiary also determines value phenomenologically.

Phenomenologically; do-doo dah do-do.

Hands up those who hear the word phenomenological, and immediately think of this following video:

Me too. But what does phenomenologically mean? Well, an example is always a good way to explore. So let’s look at the recent explosion of self-service checkouts in supermarkets. You know the ones. Where you scan your items yourself. Instead of a cashier scanning them. Or further ahead in time, autonomous checkouts like Amazon Go

Are these self service checkouts a good value proposition?

Well, first we have to get our heads out of goods-dominant logic. There we would say these self-service checkouts are great value. As a supermarket, I’m making things quicker for the customer. They also take up less space, so I can provide more of them. Why would customers not use them? And, cynically, they are cheaper for me – less equipment, less staff needed. It’s a win-win.

But in our service-dominant view, we need to think about what progress the beneficiary is trying to make. And remember this is both functional and non-functional. Functionally, I think we’d all agree it’s about obtaining grocery items for future use. But what’s the non-functional progress? Is it “as quickly as possible”? Or “be comfortable with the transaction”?

And here’s the crucial point. The non-functional progress could be different between beneficiaries. And, it could be different for the same beneficiary under different circumstances. Quickness might be valued on a rainy time-tight Wednesday lunchtime. Whereas, a big Monday evening weekly shop might make security more attractive.

So how can we capture this uncertainty? Well, we can start with value is experiential.

Value is experiential

Lush & Vargo identify that “value is experiential” in “Service-Dominant Logic: Premises, perspectives, possibilities“.

What do they mean? Simply, that the beneficiary’s experience contributes to their judgement of value. Before a beneficiary uses a service, they are judging the potential value they can create. And during/after the service, they are judging what value did they create.

However, they had a concern with using the word experience. They view experiential as implying a positive, entertaining experience. A “Disney land feeling” as they summarised. And that is not what they meant. It can be a negative experience. Such as seen in value co-destruction. Further, they wanted to steer us clear of a notion they disagree with: the experience economy.

The Experience Economy

Pine & Gilmore (1998) coined the term experience economy in their HBR article: “Welcome to the Experience Economy“. Where they see staging experiences as a step beyond delivering services. One that is the most differentiated competitive position. And commands premium pricing.

They pose the point:

Companies should think about what they would do differently if they charged admission.

Pine & Gilmore (1998) “Welcome to the Experience Economy“

And to help distinguish experience, they put it in context of the commodity, goods and service economies (Figure 2).

So, for example, the buyer should be seen as a guest rather than a client or user. And the offering should be memorable and revealed over duration.

They give several examples of experiences in their article and subsequent book (revised 2019). Such as “eatertainment” in relation to theme restaurants, or Geek Squad, Apple Stores, Disney, LEGO, and Starbucks. A deeper discussion of this would lead us into the field of experience marketing.

Should we consider an experience Economy?

Lush & Vargo (2014) problem with crafting out a new experience economy was quite simple. “Can you think of a consumption situation that is not experiential?”. They could not. And so believe there is no such thing as the experience economy.

I would say Pine & Gilmore’s work is useful. It gives good insight into that services are an experience/performance and can be memorable and personal, for example. But I agree with Lush & Vargo that experience is not a separate economy. These loop into non-functional progress – which the beneficiary maybe explicitly seeking or might find valuable once aware. Which is relevant when thinking of how to build brands that people love (enable, entice, and enrich) as well as Blue Ocean strategy.

And so, Lush & Vargo settled on the word phenomenological. Even if it is not going set the lecture tour circuit on fire, there is an academic reason for this choice.

Phenomenologically is academically comfortable

Phenomenology is the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness. And the phenomenological method is an established qualitative research method. Groenewald (2004) states the following:

A researcher applying phenomenology is concerned with the lived experiences of the people involved, or who were involved, with the issue that is being researched.

Groenewald (2004) “A Phenomenological Research Design Illustrated“

This makes academics comfortable with the discussion. Even if us mere mortals just hear the muppets singing.

But phenomenologically is a mouthful of a word; its use uncommon and is unlikely to set the business world alight with understanding and take up. Let’s talk, instead, of the lived- and living- experience.

The Lived Experience

So, if should avoid using the concept experience, and phenomenological is pretty unapproachable, what could we use instead? For me, the key is in the definition of phenomenology. From above:

…phenomenology is concerned with the lived experiences..

And “lived experience” feels a more approachable term.

But I want to break our thinking about lived experiences into two separate time slots. The first being when a beneficiary is looking at value propositions. For example, when they go to check out in a supermarket and decide between using the manned- or self-checkouts.

At this point, a beneficiary brings a set of expectations, past experience, biases etc. These are the lived experiences of the beneficiary up until this point. And they can come from a range of previous experience. Maybe of this particular service, or from similar services, or from practically anywhere.

This collections of lived experiences are individual and unique to every beneficiary. However, we may be able to tease out group-wide positive and negative lived experiences. And then leverage that knowledge in our service design to offer more value.

Yet, equally important as the baggage a beneficiary brings along, is the actual experience they have of a specific instance of service provision – the value-in-use aspect. And I will call this, the living experience.

The living experience

I will refer to the beneficiary’s experience of a particular service instance as the living-experience. This is relevant when the beneficiary chooses a service, during the service, and at the end. Once the service is over, the lived experience becomes an addition to the past-lived experience.

(I could have used the terms past-lived and lived experience here; but chose the ones I have to reinforce the value-in-use of the latest service provision).

Now we are talking aspects such as the mood of the beneficiary. What context is the service is taking place in? Is it, for example, the Wednesday lunch rush for a sandwich or the Monday evening weekly shop. Does the beneficiary feel like taking a chance on something new?

How is the beneficiary experiencing the interactions that are the heart of service provision? Is the customer service rep going out of their way to be helpful, or are responses from a disinterested person. Perhaps the Artificial Intelligent bot is frustrating the beneficiary with irrelevant questions.

Did the beneficiary want a simple, consistent, item of food but now has to navigate a menu with too many choices? Can they start using the goods straight away? Do the tires on the car need pumping up first? Does the hardware they have to play musical medium work with the media they have?

Is the servicescape – the physical and on-line landscapes in which the service is provided – helping or hindering the beneficiary make progress?

So, armed with the concept of lived and living experience, we can make the premise definition a little more approachable.

Our approachable definition

Let’s bring the above together to present a more approachable definition value:

Value is always uniquely determined by the beneficiary based on their lived and living experience

Now we still reflect that only the beneficiary can determine the value of a service. And that they do so based on the baggage they bring along – previous experiences, biases, expectations. As well as the experience they have during the use of the service – the context, their mood, interactions, servicescape etc.

Wrapping Up

OK, so “phenomenologically determined” is a valid term to use. But a bit tough if we want to get service-dominant logic mainstream. Uncharitably we could think it was used to discourage the phrase experience economy.

I believe we can instead use the more relatable phrase “lived experience”. That positions value as experienced by an actor, as part of co-generation of value, rather than a provider arranged (staged) experience.

Value is always uniquely determined by the beneficiary based on their lived and living experience Click To TweetAnd the importance of this premise is threefold. We need to be customer-centric and understand:

- what progress is the beneficiary trying to make

- what generic lived experiences of beneficiaries can we leverage (positive things) or address (hindrances)

- how we design our service and servicescape to best enable that progress and deliver the best living experience

Maybe service design is a tool to help.

Really good stuff here. I can’t help thinking that an accompanying ‘toolkit’ for determining value/benefit and establishing/factorising experiences would be extremely useful? The link between the holistic and the practical is crucial to incorporating this thinking within real-world challenges (that are themselves driven by the lived and living experiences of the reader)… begging the question, “are you musing or providing a service to your readers?”

Thanks.There’s certainly more to investigate here, for example what I’m now looking at is what does “progress” in “making progress” really mean. And how can that be “measured” – since I feel the amount of progress made by a (the) beneficiary is the real measurement of value (to them). And its probably not, as we currently think the price they are willing to pay. Plus what is this value derived from – the progress and/or some “better than now” aspect (which then pushes for adefinition of “better”…

The lived/living experience makes it hard to create a “toolkit” for determining value – since you can’t pre-determine it. But might allow for generalising aspects that suggest approaches that increase the value proposition. And perhaps that’s even different for different segments – but needs to be based on reality not imagination: I remember reading a Finnish paper on older generation use of mobile banking. Rather than technology being a barrier to use. as is often assumed, it was security of transactions.

I agree – I had a much longer response than this but it boiled down to fixing how Agile leaders measure value when progressing any activity, and consequently how that affects decisions on progress and consequent investment. I suppose the ‘toolkit’ I envisaged (and this is undeveloped thinking at this stage) is not much more than :

1) the Vision behind investment being only delivered by the beneficiary, rather than outsourced to the ‘project’ (as it often is),

2) the SoR moving from feature-driven to value-driven, with each instance of ‘value’ being established with the same degree of detail as features

3) reporting and success measurement being more a ‘church fund’ of accumulated value and the pace of accumulation rather than percentage of activities completed.

I.e. in order to develop services that feel like services and not products, repurpose the development activity itself towards continuous development of value and measure progress against this (and only this?). Some would say that this is the fundamental behind Agile but I don’t think that stacks up (mostly because of the lack of a ‘value’ measurement and reporting toolkit?).