The Big Picture…

An evolved definition of innovation – built from the observation that value is based on progress sought, offered, and realised – opens up our ability to innovate and minimise the innovation problem.

Simplistically, innovation is designing a new way to offer to help a beneficiary make the progress they are seeking better than they currently can. Understanding that progress is both functional and non-functional (safer, quicker, self-actualisation, wellness etc).

But this definition needs supplementing with the survivability of the enterprise, and aspects drawn from service-dominant logic. So we arrive at the following:

Implications

Our definition takes a service-first approach. And so innovation can only offer to help beneficiaries make progress (value proposition). Whether it does so, is determined phenomenologically and uniquely by the beneficiary in use.

The innovation has to be new. Though I include a broader understanding of new. Reflecting that innovations can be carried from use in one industry/markets to another rather than needing to only be new to the world.

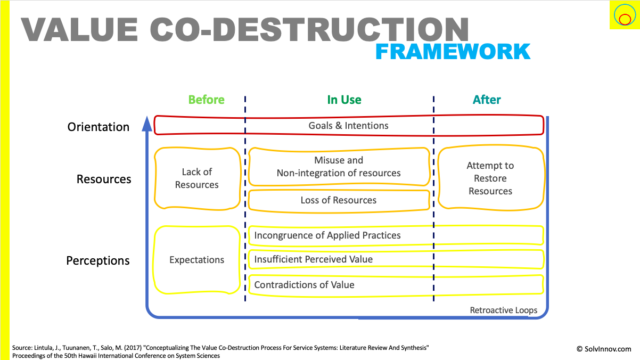

We also expect the offer to improve during use. Since value is co-created, and hopefully not co-destructed. That is to say we should aim for interaction and customisation to improve progress made.

And importantly, the innovation needs to be scalable and ensure the survivability of the enterprise. An idea that cannot scale or destroys the enterprise is not sensible. Note that I talk survivability rather than profit. Though profit is often an important additional factor to enterprises.

Finally, I add that the innovation minimises resistance and value co-destruction, as these are things we often forget to address. I can envisage these roll-out of the definition in future as they become ermbedded aspects.

And I would use the same definition for digitalisation (which is, simply, innovation where the value proposition is digital).

The Idea

We know that we have an innovation problem – 94% of executives are disappointed with innovation performance. Digging down I find one cause is the way we define innovation. And that steers how and what we innovate.

Actually, the root cause turns out to be how we define value. We tend to see manufacturers as embedding value that a customer wants. And the customer is prepared to pay money to acquire that value in an exchange. We repeatedly take a very goods-dominant logic approach – a pure focus on output and one off transactional sale to maximise return for the manufacturer. So we think of products in terms of attributes. And so most innovation relates to improving those attributes.

But we now know that we need to evolve our definition of value. And I propose one that is based around progress sought, offered, and achieved.

With that evolved view of value, can we create an evolved view of innovation? I argue yes we can, and that definition you can see in Figure 1.

Before I go through this evolved definition, let’s look at how we got to where most innovation consultants and books are today. (though if you want to jump to the evolved definition straight away, feel free to click here!)

Where are we today?

Today’s typical definition of innovation includes three aspects. Innovation:

- is a process and an output

- that creates something new/novel (where something could be products/ goods/ services/ processes)

- has value (embedded by the maker)

Over at Idea2Value.com, they summarise 15 innovation experts’ definitions. From that, they find 60% include “having or executing the idea” yet only 40% noted value to customer or business.

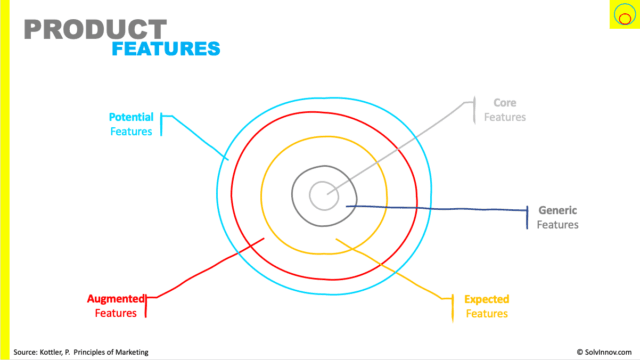

Marketing tells us that products are made of features (core, expected, augmented, etc).

And so most systematic innovation revolves around identifying new or improving existing features – the adding another razor blade effect. The attraction of, say call to actions and open innovation, is to tap into thinking outside this box. But often results of those initiatives are fed right back into that box, and our efforts stall (worse, we just perform innovation theater).

But definitions of innovation originally started off with a much wider perspective.

Schumpter’s definition of innovation

Let’s go back to the “father” of innovation. In 1934 we find Schumpter (1934) saw innovation as:

“new combinations” of new or existing knowledge, resources, equipment etc…subject to attempts at commercialization (Schumpeter, 1934)

“A Guide to Schumpter Fagerberg, 2008

Where innovation comes in five types (Schumpeter, 1934)

- launching a new product or a new species of already known product;

- applying new methods of production or sales of a product (not yet proven in the industry)

- opening a new market (the market for which a branch of the industry was not yet represented)

- acquiring new sources of supply of raw material or semi-finished goods;

- driving a new industry structure such as the creation or destruction of a monopoly position

Modern definitions of innovation

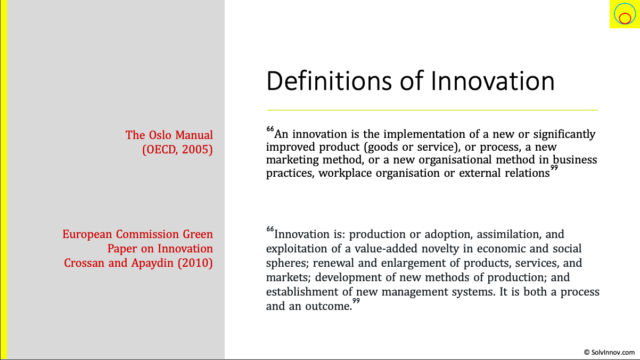

Back in 2013, Edison, bin Ali and Torkar (2013) studied innovation in the software industry and found 41 (!) separate definitions of innovation. They identified two that stood out as being best, one from the OECD and the other from the European Commission, which I have copied in Figure 2.

As we moved through 2020, the Oslo Manual updated its definition in its 4th edition (see Figure 3).

And ISO, the standards body, has produced a definition of Innovation in their ISO65000 series (too expensive for me to buy, though the definitions are aligned with the Oslo manual). Alice de Casanove, Chair of the ISO technical committee responsible for the standard, has said:

Innovation is about creating something new that adds value; this can be a product, a service, a business model or an organization. And the value that is added is not necessarily financial, it can also be social or environmental, for example”.

Alice de Casanove

So, What is the problem?

The problem with all these definitions is that they look at innovation with a divide between producer and consumer (or manufacturer/customer). One creates value, the other is seeking it and using it up/destroying it.

And, in doing so, we frame definitions through the lens of goods-dominant logic. That is to say, we:

- naturally focus on producers/manufacturers creating (embedding) value

- begin believing all innovations are good and valuable

- rely on the concept of value-in-exchange – a transactional approach that sees value as maximising cash for the manufacturer at point of sale, rather than the beneficiary benefiting.

This should not be surprising. Gallouj and Weinstein found, in “Innovation in Services“, that we have based most of today’s innovation theory on technological innovation within manufacturing companies. And so a goods-dominant logic perspective is rather natural.

However, that brings along several issues. Amongst others, it:

- makes us myopic to solutions – we want to add yet another razor blade.

- raises the risk of our innovation efforts being based on the benefit to the manufacturer/producer rather than the customer.

- minimises us building relationships with customers (our lead times are long, ability to pivot is low, and anyway we are too busy chasing the next exchange/sale).

- prevents us from seeing what the customer does with the innovation after the point of sale. The circular economy, for example, is not interesting to us (why would it be? We’ve exchanged, and making a new exchange when you’ve used up the value is good for us…). Or in job-to-be-done theory lens, we see the big hire, but none of the subsequent little hires.

This points are relevant when we consider the circular economy.

And, by believing all innovation is a good, we see only the challenges of diffusion and adoption. We pay scant regard to the very real resistance to innovation.

Are there existing solutions?

It’s not that these issues have not been recognised or partially addressed before. Levitt’s Marketing Myopia from 1969 is the warning. Yet 50+ years later, many quote Levitt but seem to carry on and ignore him.

“People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” Every marketer we know agrees with Levitt’s insight. Yet these same people segment their markets by type of drill and by price point; they measure market share of drills, not holes; and they benchmark the features and functions of their drill, not their hole, against those of rivals.

Christensen, Cook & Hall (2005) “Marketing Malpractice – The cause and the cure“

And Christensen’s Job-to-be-done theory can help us understand that people are seeking to get jobs done. So observing them and asking the right questions is a valid approach. It is indeed true that people might only ask for a faster horse (so it is claimed Ford once said about asking customers what they wanted).

Also, lean/agile approaches have arisen that help us address the transactional nature of value-in-exchange. If applied correctly. Though often they are deployed in development phases rather than observation through life.

But, somehow I find these solutions as only partial. It was not until I dug all the way down to understand what value was, did I start to find that new definition drive a new way of thinking about innovation. And also havee the foundation to those approaches.

What is innovation?

We’re not going to get too revolutionary with our evolved definition. We still base it on value. But use my evolved definition of value. And by that, I mean value is grounded in progress (functional and non-functional).

- Beneficiaries seek to make progress in aspects of their life. I call this, progress sought

- Enterprises offer to help beneficiaries make that progress – progress offered.

- And the beneficiary will integrate their resources with those on offer – people, systems, physical resources and goods – to attempt to achieve progress (progress achieved).

Now we can create a simplistic view of innovation through this lens as:

innovation is designing and offering a new value proposition that offers to help beneficiaries make the progress they are seeking, through some combination of people, systems, physical resources and goods, better than they can currently.

But this is not sufficient. We need to add understand new better, address enterprise survivability and draw in the appropriate aspects of service-dominant logic. Here, then, is my proposed definition (in Figure 4).

OK, let’s dig into what this means, and why!

Innovation is designing and offering a value proposition…

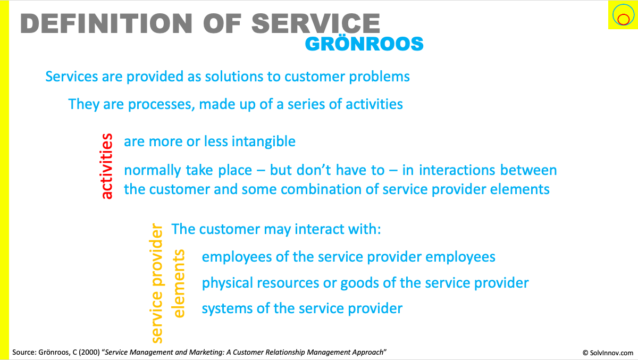

Right from the start I want to anchor the definition in service-dominant logic. And that tells us that:

Actors cannot deliver value but can participate in the creation and offering of value propositions

Foundational premise #7 of service-dominant logic

So, we, the innovator, can only ever offer a value proposition, and not something that we see as having embedded value (which is our old goods-dominant way of thinking). This applies equally to service and goods. In fact, it is important to note that we should see no difference between goods and service, as I’ll cover shortly.

In common with other definitions of innovation, innovation is an act of creativity. So it is the act of designing the value proposition as well as offering it. And that means there has to be an element of novelty.

…that is new to the organisation, market/industry, or the world

I take a broad view when defining new. Rather than needing an innovation to have never been seen before, I leverage Edison, bin Ali and Torkar’s (2013) definition of novelty (from “Towards Innovation in the Software Industry“). Only altering slightly to use enterprise instead of firm, so as to include, for example, non-profits.

New to the world is probably what most of us would think an innovation needs to be. That is to say, no-one has seen it before. In such a case, we could say, as den Hertog does, that the inventor is the source of innovation (“Knowledge-Intensive Business Services As Co-Producers Of Innovation“).

But, increasingly we look to other markets and industries to see what solutions they have that could be useful in our own industry/market. Here den Hertog talks about carrying innovation. And beneficiaries are a driver here. They increasingly expect to do in your industry/market things they already can in others they interact with

QR codes are a good example. Once established as an innovation in event ticketing, they rapidly spread to the travel industry – long gone are the old paper tickets for flying with their quaint carbon copy paper inserts!

Finally, innovation can be new to your enterprise. Implementing a new tool or process that is used in another organisation can still be new/novel.

The Value Proposition helps the beneficiary make progress…

Here we reach the heart of the definition. Beneficiaries are seeking to make progress in some aspect of their life. They don’t really buy products or services; they “hire” them to make progress. This is close to Christensen’s view of job-to-be-done. As well as mirroring Levitt’s warning about customers wanting a 3/4 inch hole, not a 3/4 inch drill.

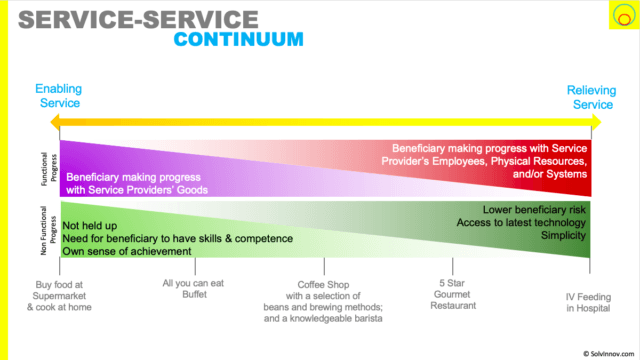

So a value proposition has to offer to help beneficiaries make the progress they are seeking. This means we need to know what that progress is. And that progress can be functional and/or non-functional.

First, there is functional progress. We can think of this as the direct outcome of the progress. I need to fill my time during my commute, for example. Or, I need to hang this picture onto this wall. What am I trying to get done, what hinderance an i trying to overcome our problem an i solving?

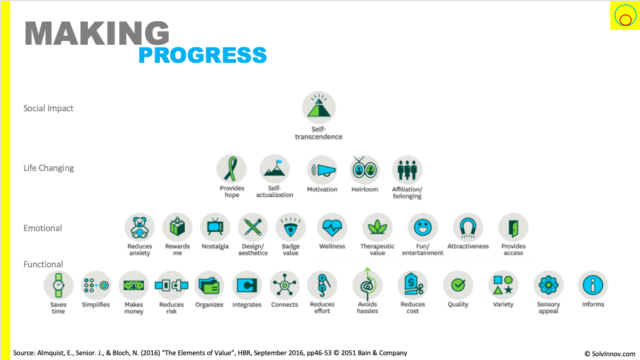

Secondly, there is non-functional progress, here we can look to “The Elements of Value“, by Almquist, Senior & Bloch. They give us a useful hierarchy of several non-functional elements of progress beneficiaries might be seeking.

But, for our innovation to be on the way to being successful, the beneficiary needs to see some advantage.

…better than they can currently

We need to offer to help beneficiaries make that progress better than they can currently. If we offer a way of making worse progress then we challenge our ability to be successful. And if we offer the same progress as others, why would the beneficiary switch? Remember, that we are thinking more abstract with progress than selling a 3/4 inch drill. And an option the beneficiary has is “do-nothing”, especially if their current options are not good enough.

So to be an innovation, we not only need to know the progress they are seeking, we have to offer to help them make that progress better than they currently can. And that better could be in the functional or non-functional axis, or in both.

However, we know that value (progress achieved) is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by only the beneficiary.

Value is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

Foundational premise #10 of service-dominant logic

Where “phenomenologically” refers to the lived and living experience of individuals. Think of supermarket self-scan checkouts. I might see value during a busy lunchtime rush when I want to buy only a sandwich. Though less value in my weekly shop. Others may never see how it helps them make progress in purchasing items with a reduced-risk of being accused of theft. This ties in to a later point about looking past the point of sale and relations we need to bring.

Offering more progress or worse progress?

We could offer more progress than the beneficiary is seeking. Like Apple often does with technology in new releases of iPhones that have no current market need (but soon find it). Or we could spot some progress that the beneficiaries are not truly aware they are trying to seek and offer that.

And we could even offer worse progress. We might do that if we can’t meet all progress sought, but are confident that beneficiaries are willing to compromise. Or perhaps we are worse in some aspects but offer more in others.

There is an exception around offering “worse” progress. It might be deliberate when we truly are trying disruptive innovation (an often misused term). In this case, we are offering “worse” progress to the current market but good-enough progress at the lower end with a view to move upwards and displace incumbents. This “worse”, though, is only in relation to how we have defined the progress sought (since for the lower end our progress offered is good-enough).

It improves as a result of co-creation of value

We improve on the goods-dominant logic by realising that value is not embedded by a creator to be sold at exchange. Rather, value is co-created in use. As foundational premise 6 of service-dominant logic tells us.

Value is always co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary

Foundational premise #6 of service-dominant logic

This means we, as an enterprise, need to look beyond the point of sale. And that means getting relational with the beneficiary (individually or as progress seeking segments). When we do, we align with service-dominant logic’s foundational premise #8.

A service-centric approach is inherently beneficiary oriented and relational

Foundational premise #8 of service-dominant logic

The point of this is that our innovation should improve as a result of this coming together, relational approach to co-create value. Christensen’s job-to-be-done theory talks of a “big hire” – when the beneficiary switches to explore our value propositions – and “little hires” – the repeated choices to re-hire our value proposition again. To keep the little hires, we need to react to changing customer expectations as well as market changes.

This looking into the co-creation of value will give us even deeper insights. And is crucial if we are to address a non-functional aspect of progress that is becoming more important to more beneficiaries: support the circular economy. Can we make changes to our offer that enables re-use, re-purposing, sharing economy, re-manufacture etc?

And is delivered in a scalable and sustainable way…

We can’t forget that our innovation has to be scalable to the market size we anticipate.

And that it has to sustain the enterprise. Note that I don’t use profitable here. That for sure is an additional factor typically for commercial firms. But I want to include all types of organisations, for example non profit. And so sustaining the enterprise is sufficient.

…co-ordination of skills and resources

From service-dominant logic we know that service (including goods which are a way of distributing service) is really an act of resource integration.

All social and economic actors are resource integrators

Foundational premise #9 of service-dominant logic

And these resources capture skills.

…captured in some combination of actor’s resources

Any service – and remember we see goods as a distribution mechanism for service (often self service) – is an interaction of the beneficiary with some combination of employees, physical resources, goods and systems. Each of which capture skills necessary to help progress be made.

Altering the combination of employees, systems, physical resources or goods is a source of innovation. Effectively we slide along the service-service continuum.

And this definition of service helps us understand the positioning of goods. We don’t have a good vs service world. Where we are comfortable with goods and define services from that viewpoint (often as poor relatives). Instead we recognise service-dominant logic’s 3rd foundational principle:

Goods are distribution mechanisms for service provision

Foundational premise #3 of service-dominant logic

Think of the progress of quenching thirst. You can take water from you tap/faucet (generally seen as a service, through systems) or grab a bottle of water (generally seen as a goods). There is no Goods vs service debate here.

…often in an ecosystem…

But we rarely deliver a value proposition in isolation. Nearly all offerings involve an ecosystem. We have payment partners, distribution partners, and so on. Ecosystem scalability and sustainability is increasingly important in our own offerings.

And ecosystem can bring innovation to our service, either by adding new partners or replacing existing ones.

Where the resistance to innovation is minimised

And finally, we know that innovation resistance – where the use of an innovation is postponed, rejected, or even opposed – is a big issue. But amazingly, it is rarely thought of or addressed today. So, to remind ourselves, I add this to my definition.

…and Value co-destruction is also minimised

Along with the need to minimise potential for value co-destruction.

Wrapping Up

And so, we have our evolved definition of innovation. One that is grounded in service-dominant logic, rather than the usual product-dominated logic approaches that underpin today’s innovation problem.

What is innovation?

Innovation is creating and offering a new (to the organisation, market/industry, or world) value proposition that:

offers to helps beneficiaries make functional and non-functional progress they are seeking better than they can currentlyimproves during, and as a result of, the naturally occurring value co-creation

is delivered through the scalable and sustainable co-ordination of skills and resources (captured in some combination of people, systems, physical resources and goods), often across an ecosystem

and where resistance (opposition, rejection, or postponement) and value co-destruction have been minimised