The Big Picture…

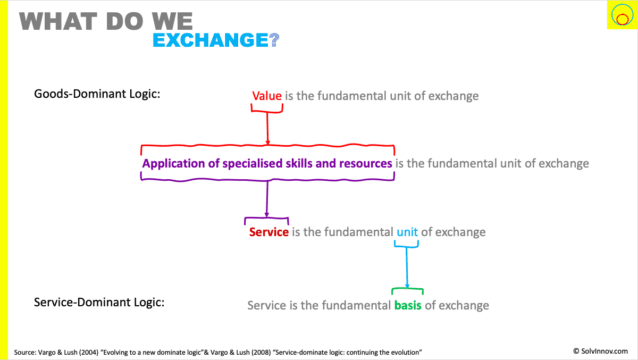

We get better insights into innovation when we look at the world through a lens that observes we exchange how we arrive at outcomes (service) rather than those outcomes themselves (products). That is to say, service is the fundamental basis of exchange (rather than value).

And this is the 1st foundational premise of service dominant logic.

The alternative – which is how we are taught to view the world – is a lens where we see goods are exchanged for value. This lens focuses heavily on that point of exchange. And that challenges innovation and growth in several ways, including that it is not relational, the producer feels they determine value, they become myopic in improving offerings (the ” one more razor blade “ problem) and they miss post-sales opportunities, including the circular economy.

I still struggle sometimes to grasp this view of service being exchanged. But here’s a way of thinking that should be quite familiar. We often will do a favour for a friend. And the implicit/explicit expectation is that they will return that favour, at some point in the future. This is service exchange.

Implications

Using a service-dominant logic gives us a lens where the blind point of value-in-exchange doesn’t exist.

We can start to see value in terms of the progress a beneficiary is trying to make. And how we can offer to help them. We are encouraged to think past the challenges goods-dominant logic presents – minimising myopia and lost opportunities.

We find opportunity for innovation and growth.

Though, we need to appreciate that such direct exchanges, such as our friends swapping favours, are hard to observe in reality. And that is often because indirect exchange masks service exchange. Where cash, as a form of service credit, lubricates this indirect exchange.

Now, I’m not saying that one lens is more correct than the other. They are not instructions on how the world works. But I propose that using a service-dominant lens gives us a better opportunity to hunt for innovation and growth.

This premise was given axiomatic status by Vargo & Lush (2016). That is to say, a number of other foundational premises can be derived from it.

The Idea

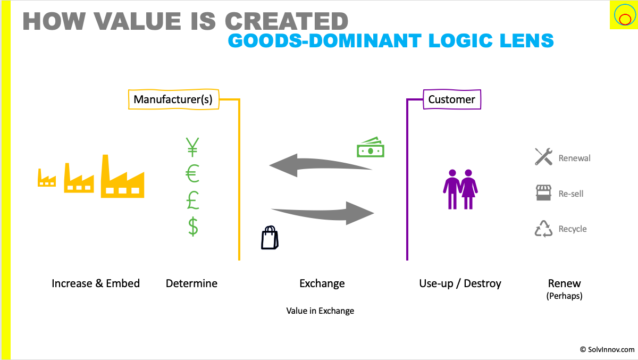

Today we tend to see, believe, and are often taught that the logic behind economics is one based on exchanging products (predominately goods) for value. Manufacturers take various inputs and embed value as they produce an output. And we have chains of manufacturers, each adding their own value along the way. These same manufacturers determine the value of their output. And are eager, and very much focused, on exchanging their output (value) generally for cash. Moving on swiftly to hunt the next exchange.

Meanwhile, the customer is typically using-up or destroying the value they’ve just acquired. The chocolate bar is eaten; the car wears out through use, etc). Though the manufacture rarely is interested in that or what might happen next. The customer might be able to renew some value. Perhaps restoring the goods, reselling it, or recycling.

But this logic lens is failing us – we find innovation and growth hard to find. There are only so many razor blades that we can add before the consumer sees parody rather than value. And in reality, we see that service is eating the world.

An alternative logic – service-dominant logic – sees service as the basis of exchange. That is to say the act of creating output rather than the output themselves. It is the 1st foundational premise:

Service is the fundamental basis of exchange

Vargo & Lush (2004) “Evolving to a new dominant logic“

And this has positive outcomes on how we think about value and therefore, innovation and growth.

Let’s explore why value-in-exchange leads to a logic that is a poor lens for innovation and resulting growth.

Why is value-in-exchange a poor proposition for innovation and growth?

Early economists developed goods-dominant logic when attempting to turn economics into a science (according to Vargo & Lush “Evolving to a new dominant logic“). Although it wasn’t called that until we needed to name it as we started exploring alternatives. Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, certainly saw that manufacturers produce wealth, services do not. And from then on, goods and manufacturing have underpinned economics thinking. Not least that we’ve ended up defining services as poor relations to goods (which they probably are not).

The fundamental aspect of goods-dominant logic is that concept of value-in-exchange. Most obvious, from above, with the manufacturer’s focus on exchanging their goods that they have embedded value in for cash.

I suggest this makes innovation and growth more changing that it needs to be. We (as manufacturers):

- lack relationships

- we can miss what the customer really needs

- we can miss understanding if the customer saw the same value as we did

- are encouraged to miss post-sales opportunities, we:

- focus so much on maximising cash exchange and making the next exchange

- miss opportunities after the sale for growth

- fail to appreciate the circular economy

- see (or rather, often don’t see) this is the manifestation of marketing myopia –

- driving us to think only in terms of the existing solutions – the so called “one more razor blade” problem

- we can miss wider opportunities of altering the service mix (goods, physical resources, systems and employees)

- carry on the negative misunderstandings of service – e.g. they are inconsistent instead of seeing that as customisable, etc.

Let’s dig into a few of these in more detail.

Lacking relationships

Have you heard of Juicero? It’s an example of where an inventor thought they had a great idea but hadn’t really understood the customer. It turns out, no-one really needed a pod-based juicing machine. Although you can imagine that the inventors thought it would match the success of Nespresso, perhaps for a more health-conscious market.

When you don’t have relational interactions with your beneficiaries, then this type of failure can happen. And it’s not alone, the Sinclair C5, Segway and others all sit in this hall of fame.

Despite a plethora of marketing gurus and theories telling marketers to understand customer needs, we still get these failures. We often think we talk to our customers to find their needs. And translate those to new and better attributes and features of products – just like the marketers tell us.

But in goods-dominant logic, we get a bit blinded. We, as manufacturers believe we determine value. Remember, Juicero was at some point seen by the inventors and investors as valuable. And all that marketing then need to do is persuade customers it is.

And we try our hardest not to customise the product as that reduces our margins (unless we can find a way to charge a premium…).

When it comes to satisfaction in use, the volume of sales will tell us how well customers are receiving our product. Even if customers are quite happy using 3rd parties to vent frustrations (e.g Trustpilot). This leads, like it or not value co-destruction.

Missing post-sales opportunities

Another challenge with this focus on value-in-exchange is that it doesn’t encourage us to look at what the customer does after the point of sale. It doesn’t mean we never do, we’re just not encouraged to. As there’s the next sale to make, etc.

I’m not thinking of the potential value co-destruction from above. What I’m thinking about is the right-hand part of Figure 1. Where customers are trying to renew value they have used up/destroyed. Perhaps they ate trying to refurbish, renew their product. Or they might be trying to resell it. By being less interested after the exchange, we are leaving growth opportunities on the table.

And this ties into the circular economy. If we’re not thinking past the point of exchange, it’s unlikely we are designing our products to be recyclable, refurbish able etc.

Being Myopic

Value-in-exchange encourages us to be limited in our vision for innovation. It drives a manifestation of Levitt’s “Marketing Myopia“:

“People don’t want a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole”

Gallo, A (2016) A Refresher on Marketing Myopia

If we are myopic – short sighted – then we keep on trying to provide and improve a quarter-inch drill. We can call this the adding yet another razor blade syndrome. And that eventually leads to failing enterprises.

But, there are many ways to offer creating a quarter-inch hole. Some are going to be incremental. Others, more radical changing our approach and enterprise make up.

Myopia will blind us to opportunities such as servitization.

Misunderstanding service

Finally, a goods first approach leads us to define service as a poor relative of goods. They are intangible, inconsistent. And we can’t create an inventory. Worse, we need customer involvement and insearable.

This makes us steer towards goods as they are tangible and we believe we know what to do with them. Limiting our view of growth.

The Answer: service dominant logic is the fundamental basis of exchange

So, goods-dominant logic is one lens through which we can observe how the world works. Its basis is outcomes and what they are exchanged for. But we could use a different lens. One that sees the exchange as being the act of creating the outcomes, rather than the outcomes themselves. And this is service-dominant logic.

Now, I think it is important to realise these are not competing instructions on how the world works. They are lenses – a way of getting insights. Each is useful for different purposes. As we’ve heard, goods-dominant logic was useful to early economists and has theorists since,

My hypothesis is that service-dominant logic is the best lens to look for innovation and growth.

However, this thinking can be a little challenging. So lets see what we mean by exchanging service.

We Exchange Service?

Exchanging service might, at first glance, go against everything we know. After all, we’re very used to paying cash for almost everything.

But, exchanging service is old school. As societies evolved, people specialised. Some might become farmers, some fishermen, some soldiers, some kings (administrators/leaders/protectors). And with specialisation, comes exchange. Kings provide protection for farmers. In return farming provides food sources. Whereas a farmer is unlikely to protect and a king unlikely to farm.

Though even today, this is not as strange as it may first sound.

For me, it’s easiest to think through an example. And I believe we’re all familiar with doing a favour for a friend. That’s to say, helping a friend with something where they are seeking to make progress. And we do that by applying some (specialised) skills and competence we have for their benefit. We’ll shortly see that this is our definition of a service. So we are performing a service for our friend.

And it’s not unreasonable to expect that our friend will return that favour to us in the future. They will perform a service for us. Applying some (specialised) skills and competence they have for our benefit.

Of course, there’s a risk in friendships that the favour is not returned. And we could debate if the skills and competences are truly specialised – helping each other move house, for example. But we’re really splitting hairs on this example. In truth, we have exchanged service.

There is a key point from this example that is worth highlighting.

The exchange may not be immediate or direct

You probably have noticed that the service exchange between our friends is not immediate. “…our friend will return that favour to us in the future.”. Of course, the favours could be swapped immediately, but usually, there is a gap in time. This is unlike value-in-exchange where you hand over cash and get the product directly.

Does this matter? Not really, remember logics are not instructions on how something works, rather a lens. The key point here is that we observe service is exchanged. And this is defined as axiomatic to service-dominant logic by Vargo & Lush (2016). That is to say, a number of the other foundational premises can be derived from it. And some of those derived premises help us understand this gap (for example, indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange)

Before I jump into exploring why exchange of service helps us find innovation and growth, let’s refresh ourselves on what a service is.

What is Service?

I dig, in detail, into what service is in this set of articles. In short, Vargo & Lush define service “as the application of specialized competences (knowledge and skills) through deeds, processes, and performances for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself”.

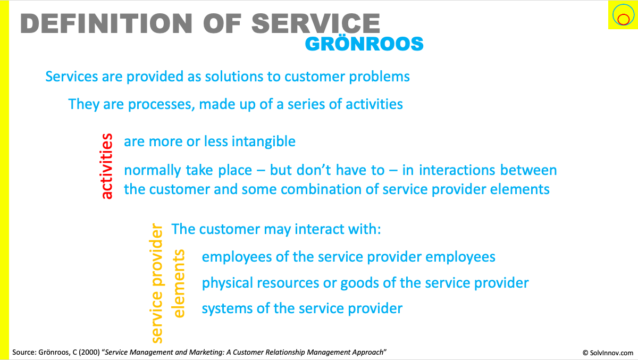

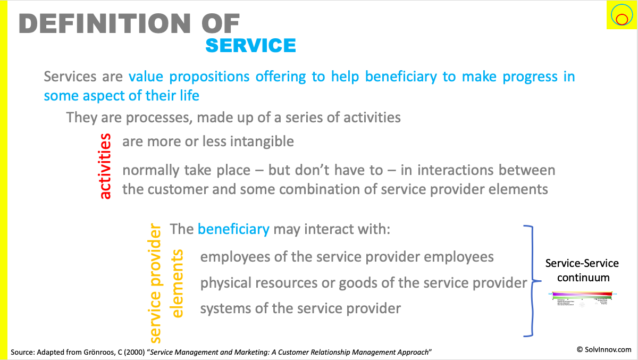

Although I prefer the more actionable definition of service given by Grönroos in Figure 2. Luckily, Vargo & Lush see these two definitions as compatible (“Evolving to a New Dominant Logic”, 2004).

It is important you see that we are not defining service in a typical way. That is, by first defining goods and then indicating why service is problematic to that definition. Rather this service-first definition sees goods as one possible element of four, that the customer (beneficiary) may interact with.

So, employees, physical resources, goods and systems all capture various specialised competence. And enterprises would offer a particular combination of those as a solution to customer problems. We actually see goods as freezing service for distribution.

And hiding things a little more is that indirect exchange mask this service exchange. This is the subject of its own foundational principle. But what we mean is that real life is a little more complex than always one-one service exchange. And we can see cash as service credits – the right to future service – facilitating these more complex service exchanges.

Aren’t services bad things though?

Vargo & Lush have a great article busting the marketing myths of service:

Unless tangibility has a marketing advantage, it should be reduced or eliminated if possible

Vargo and Lush (2004) “The four service marketing myths“

The normative marketing goal should be:

a. customisation rather than standardisation

b. to maximise customer involvement in value generation

c. to reduce inventory and maximise service flows

The benefit of believing we exchange service

Though the lens of a logic that removes the point of value-in-exchange brings a host of benefits.

Moving away from value-in-exchange thinking and towards service thinking brings many benefits. We map much closer to the evolved view of value; we’re more relational with the beneficiary; myopia is reduced; and we see past the point of sale.

It’s relational

Service-dominant logic is inherently relational and beneficiary oriented. There is a dialogue expected before the beneficiary and other actors integrate. Where the beneficiary determines if the value proposition is going to help them make the progress they are seeking (or perhaps enough progress). And where the other actors could customise the value proposition to offer even greater help in the beneficiary’s progress.

Similarly, as the act of service progresses, there needs to be more dialogue. The beneficiary is constantly reviewing the progress they are making with the help of the value proposition. And they do that uniquely and phenomenologically. They may require changes. Or the other actors may spot better ways to offer progress.

This relational aspect allows us to see past the point of sale. We get to observe that maintenance and logistics are after-sales challenges that we might be able to help with by moving towards servitisation. Or that the circular economy is becoming an increasing aspect beneficiaries wish to make progress in.

We observe that value is co-created in use.

Value is co-created

Unlike with goods-dominant logic lens, where value is created and determined by manufacturer, our service-dominant logic lens sees value as co-created.

This maps well to my evolved view of value. That revolves around progress sought, offered and achieved. Where everyone is seeking to make progress with various aspects of their life. And a variety of enterprises, including the “do nothing inc.”, are offering to help people make that progress (progress offered).

Progress is made together when a beneficiary decides to integrate with the elements of a value proposition. And progress equals value. So value is co-created.

As Ballantyne & Varey’s paper “Introducing a Dialogical Orientation to the Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing” puts it, dialogue underpins co-generation of value through:

- communicative interaction,

- relationship development, and

- knowledge application

Co-creation of value allows us to reach into the magic world of agility.

Myopia is reduced

We reduce the opportunity for myopia in innovation. Rather than “how much can we get at exchange” our question opens up to “how can we help beneficiary make progress?”. We’re truly looking at how to help the customer make a quarter-inch hole.

And this is actually baked in to our definition of service. Where the last part identifies the service mix. A source of innovation is altering that mix. For example, moving from a goods based mix, that typically indicates an element of self service on the beneficiary’s side. To a mix that has more of the other elements.

A beneficiary might want to make progress of travelling from city A to B. They are on their own. A goods mix would be selling a car. But other mixes are hiring out a car (physical resources, systems and often employees). Or a peer to peer platform to connect travellers with free seats in cars (system). Or…

Finally, Vargo & Lush (2016) notes, we are still talking “in terms of units of output, whereas service-dominant logic revolves around processes”. And so we say that service is the fundamental basis (rather than unit) of exchange.

Wrapping up

So, we have two lenses we could see how the world works. One looks at outputs and concerns itself with a moment of exchange. The other concerns itself with exchanging how outputs are created.

The former challenges growth/innovation. We risk becoming myopic, un relational and focus on making sales, missing the opportunities that lie past that point of exchange.

Instead, a logic lens that focuses on exchange of service opens up the world of innovation and growth.

However, using the service-dominant lens can be uncomfortable initially. Since we naturally observe value-in-exchange in our everyday world with the use of cash. And our economic theory has grown from and grows such thinking.

The answer to these issues, in our service-dominant logic lens, is that direct service exchange is masked by indirect exchange. And that cash is really service-credit that facilitates that indirect exchange (as well as arbitrating between size of services exchanged)