The Big Picture…

Adoption is when an individual, or organisation, decides to use your innovation. And it is a classical theory in innovation. This theory identifies 5 adopter types. And you may have heard of them, such as early adopters and laggards. Additionally, Rogers’ identifies adoption as a five-step process: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation.

However, this classic theory assumes innovation is good and is just waiting to be adopted. And, in reality, we come across innovation resistance. Where adopters could postpone, reject or outright protest against innovation based on a set of attributes. Just think of the first version of Google glass or Segway.

I include resistance and combine insights from Christensen’s Job theory to arrive at an updated adoption decision step (swipe between the original and updates below).

Rogers also identifies that by addressing 5 variables we can accelerate the rate of adoption in a group. And these variables are:

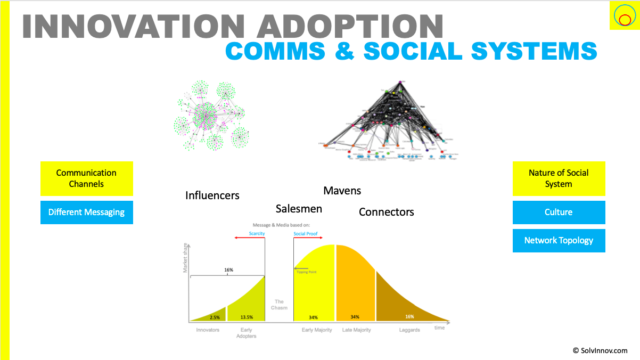

- communication channels

- nature of the social system.

- perceived attributes of innovation,

- type of adoption decision,

- extent of change agent’s efforts.

I suggest we need to add a 6th variable. And that is to minimise innovation resistance. So, we end up with the following:

There are interesting challenges when it comes to platforms – think Tinder, Uber, Air b’n’b etc – where you have two or more adopter groups. Each group is different. But adoption by one group also depends on how much of the other group has adopted.

Implications

The adoption theory gives us many things.

As an innovator, the perceived attributes, and additional resistance minimising attributes, are things we need to address. We need to look at how to take advantage of communication channels and the nature of the social system. We have to understand the type of innovation-decision and how to influence within that (or change it). And how to influence the change journey.

If we are trying to implement an innovation in an organisation, then we can ensure the right change happens. Perhaps influencing the communication channels and social system. And we can leverage the perceived/resistance attributes as part of the change journey.

Adoption is closely related to diffusion.

What is adoption?

Innovation adoption is the act of individuals or organisations deciding to, and starting to, use an innovation.

getting a new idea adopted, even when is has obvious advantages, is difficult

Rogers (2003) Diffusion of Innovation

In this article, I explore two main topics. First, what does adoption mean for individuals and organisations? And secondly, can we speed up adoption; if so, how?

I look at adoption from the classic product view, as well as for platforms. Where platforms need two or more sides to adopt to be useful. Along the way, we’ll look at Rogers’ adoption curve, adopter types and Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Decision Process. And I’ll enhance the adoption decision process to show where innovation resistance gets addressed.

Let’s get adopting!

Adopting

In a moment we’ll watch a video that shows Rogers’ adoption curve in action. But first, I’ll introduce his curve – take a look at Figure 1.

So what does this curve tell us? It shows how many of your target market have adopted your innovation at any particular time. And it usefully breaks down adopters into 5 adopter types – innovators, early adopters, early and late majority, and laggards.

These adopter types can be broadly defined as:

- Innovators – the risk-takers who are excited by new things and are about 2.5% of your target market

- Early adopters – trendsetters/influencers, around 13.5%

- Early Majority – the pragmatists, around 34%, and start adopting when they see your innovation as mostly stable

- Late Majority – the cautious, another 34%, who need proof that innovations are working and in widespread use

- Laggards – the sceptics who love the status quo and are going to require a lot of change work to adopt

You probably recognise yourself in one of the above categories. And maybe even see yourself in different categories depending on the type of innovation.

OK, enough of the writing. You can see all these adopter types in action in the following video:

Relationship with diffusion

There is a relationship between adoption and innovation diffusion.

Diffusion – is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

Adoption – getting a new idea adopted, even when is has obvious advantages, is difficult

In fact the two are very closely related. If an innovation doesn’t diffuse, no-one knows about it, so adoption doesn’t happen. And if people don’t adopt, then diffusion comes to a halt as no-one sees it in use or reads reviews etc.

It’s therefore useful to understand diffusion. And in particular how it looks/works within a network. I do that over in this article. Where we come across Bass’ model, crossing the chasm, the 16% rule, tipping points, influencers, mavens and more. The structure (topology) of the network may also help understand / be used to help diffusion. And we’ll see shortly that network – in the form of social system and communication channels – are an accelerator of innovation adoption.

Problems with Adoption theory

Adoption theory works really well. And we know that it can predict with fairly spooky accuracy real-life.

But, it assumes that the innovation is good. And is just waiting to be adopted. That’s not always the case. The innovation might be offering to help beneficiaries make progress in some aspect of their life that they really are not that interested in. Segway is an example. No one was really seeking the progress it offered to help with. Google glass another example.

And the theory does not explicitly take into account innovation resistance. Which is where innovation is not adopted immediately. It may be postponed, rejected or even objected to. Worryingly:

- “innovation resistance seems to be a normal, instinctive response of consumers” (Sheth and Ram, 1989)

- customer resistance is usually one of the most significant risks to innovation (Heidenreich & Kraemer, 2015).

As we look at adoption below, I will bring innovation resistance into the classic theory. Lets first look at how the decision to adopt an innovation happens.

Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Decision Process

Rogers observed that people/organisations decide to adopt using a 5-step process, in Figure 2.

Let’s take a look at each step, starting with Knowledge.

1 – Knowledge

The first step of the adoption decision process is part of diffusion: gaining knowledge of the innovation. Rogers breaks it into three types: awareness, know-how and know-why knowledge.

knowledge occurs when an individual is exposed to an innovation’s existence and gains an understanding of how it functions

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

Perhaps you actively seek out an innovation to help you make progress with something in your life (get a job done, solve a problem, or reduce a hindrance you have). Or you become passively aware through a magazine article, trade-fair, or observing someone in your social network using the innovation, etc. Either way, you are getting awareness knowledge.

If you find the innovation interesting enough, then you seek know-how knowledge. You want to know how to use the innovation correctly. If you’re still interested, then you tend to enhance this know-how knowledge into know-why knowledge.

Armed with your new knowledge, you probably go to the next adoption decision step: persuasion.

2 – Persuasion

Now, in the persuasion step, you are gathering more information and forming favourable, or unfavourable, attitudes towards the innovation. You are starting to move from logic to more feeling-based decisions.

persuasion occurs when an individual forms a favourable or unfavourable attitude towards the innovation

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

A part of persuasion is the beneficiary determining the amount of proposed value – how much (functional and non-functional) progress the value proposition will help them make.

As well as where they begin to weigh up various attributes of the innovation. Rogers identified 5 variables that we will look at soon that affect speed of adoption. These start to make an influence now. As does any resistance to the innovation you may start feeling.

But, “the formation of a favourable or unfavourable attitude toward an innovation does not always lead directly or indirectly to an adoption” decision, notes Rogers.

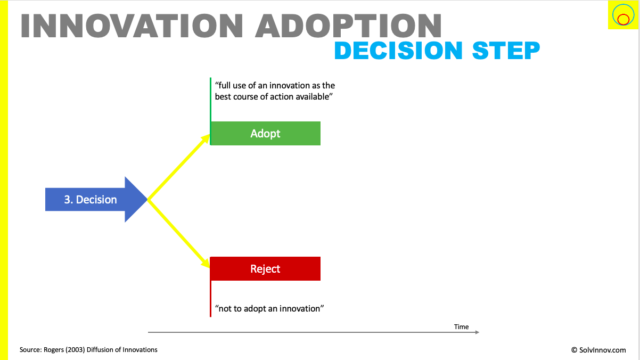

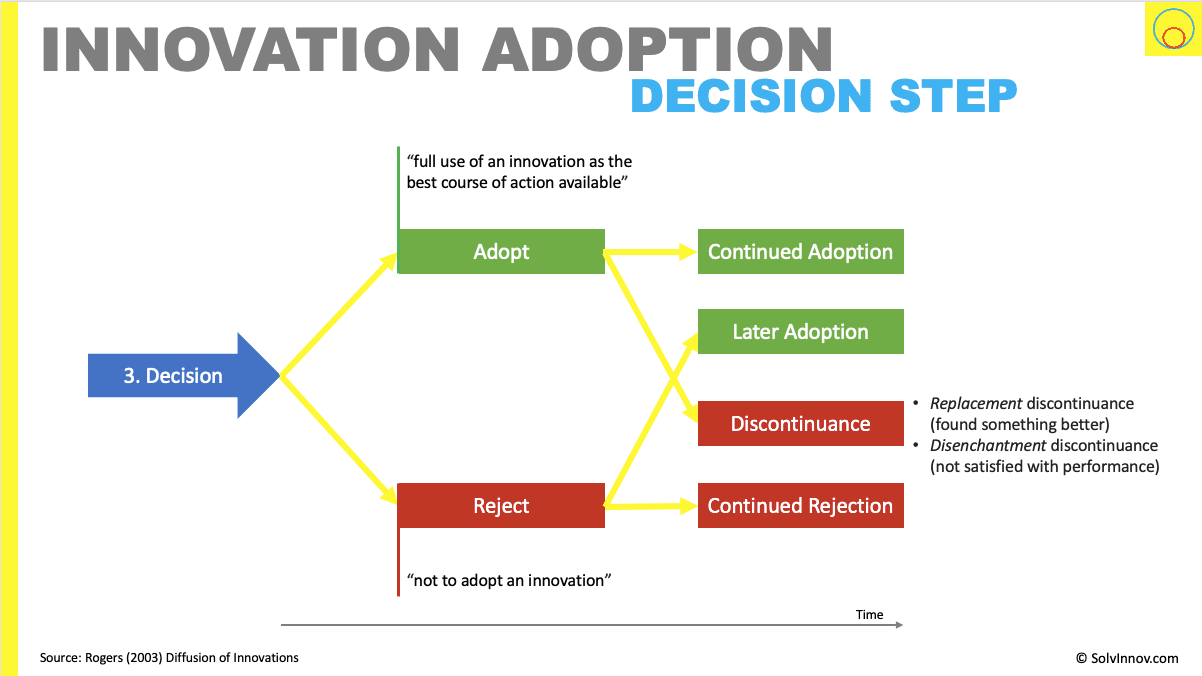

3 – Decision

Once you’ve gained your knowledge and have formed an attitude towards the innovation, you are now in the decision step.

Will you decide to adopt – you choose “full use of an innovation as the best course of action available”? Or will you reject it now, i.e. chose “not to adopt an innovation”? Which we will call passive rejection.

But your decision is likely to be more complex.

Addressing Discontinuance

You might choose to adopt and then later decide to reject.

Rogers calls this active rejection (also known as a discontinuance). And we typically actively reject for two reasons. Firstly, we realise after some time that we don’t get the benefit we expected. We call this disenchantment discontinuance. Secondly, we may discover another, better innovation – a replacement discontinuance.

Insights from Job Theory

We can draw a link here to Christensens Job theory. Where we hire something to help us make progress. But there is a big hire where we first decide to and use the innovation. And then subsequently little hires where we use it again. At each little hire point we make a decision. Do we hire the innovation again (continued adoption), or hire something else that helps us make progress better (replacement discontinuance), or not use the innovation (disenchantment discontinuance).

Similarly, we might initially reject an innovation but later decide to adopt it due to some change in circumstances. Here we can take an insight into innovation resistance to see why.

Handling Resistance to innovation

Too often we forget – or worse, don’t even know we have to address – innovation resistance (which I explore in this article). We tend to take the view that innovation is a good thing, and so we only have to persuade actors to adopt. But this misses that adopters can, and often do, resist innovation. Worryingly:

Luckily, we know from Ram’s “A Model Of Innovation Resistance” article that “adoption begins only after the initial resistance offered by the consumers is overcome”. As such, we can update our view of the decision step to that shown in Figure 4.

If we do decide to adopt and have overcome resistance, then it is time to implement.

4 – Implementation

You start using the innovation in the implementation step. But adopters may still require assistance from change agents to reduce any remaining uncertainty.

It is also at this stage that reinvention may occur. Where a user modifies, or changes, a particular innovation as they adopt and implement it.

reinvention – the degree to which an innovation is changed or modified by a user in the process of its adoption and implementation

Rogers (2013) – Diffusion of Innovation

Reinvention is common in the software tools industry. Where, for example, a generic tool is implemented and then customised for a particular client. Say to fit with the clients’ processes (rather than the client adopting the tools standard process flow).

5 – Confirmation

Finally, the last step of the adoption decision process is where the user seeks confirmation about their decision to adopt.

So that’s the process. Let’s now consider if we can increase the rate at which adoption occurs.

Increasing the Rate of adoption

Rates of adoption are naturally increasing. Just look at Figure 5 (from this HBR article). And you see that while the telephone took 60 years to get to 80% adoption in US households, adoption of mobile/cell phone took a mere 14 years.

Rogers defines the rate of adoption as:

rate of adoption – the relative speed with which an innovation is adopted by members of a social system

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

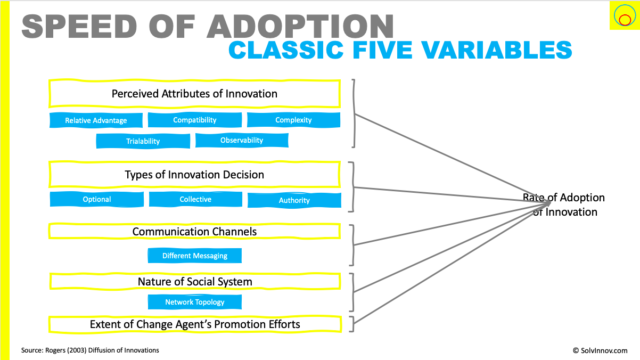

And he further identified five variables (see Figure 6) that affect the rate of innovation adoption. These are:

- Perceived attributes of innovation – relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability

- Types of innovation-decision – optional, collective, authority

- Communication channels

- Nature of the social system

- The extent of change agent’s promotion efforts

Let’s look at each of these in turn, starting with the types of innovation decision.

Types of Innovation Decision

We tend to see the adoption decision as an individual choice – an optional innovation decision. Even if group dynamics play their part (peer pressure). But there are two other types of innovation-decision: collective and authority.

A collective innovation-decision is where the social network together chooses to adopt an innovation. We can see such choices as consensus taking. Sometimes this consensus approach creates new social networks forming around an innovation (Linux operating system, for example).

And an authority decision is one where either an external influence or someone in the group takes and enforces a decision to adopt. Legislation or regulatory decisions can drive these type of decisions. Though most often, it is organisations internally deciding to adopt. For example, a CFO deciding to implement a new finance system, that impacts everyone in the organisation.

Authoritarian decisions place a high emphasis on the efforts of change agents.

Perceived Attributes of Innovation

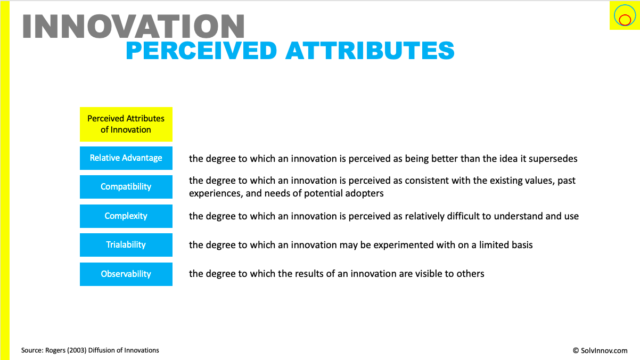

Rogers identifies there are five, what he called, perceived attributes of innovation that affect the rate of adoption. These are:

- Relative advantage

- Compatibility

- Complexity

- Trialability

- Observability

Let’s take a look into each of them.

Relative Advantage

How is this innovation better than the existing solution?

the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

My modern, service-dominant, definition of innovation talks about how it needs to help the “beneficiary make progress, better than they can currently”. And Vogt (2013) talks about what “better” might be. There it is defined as adding in at least one of several sub-dimensions: economic profitability, low initial cost, savings in time and effort, the immediacy of reward, status, etc.

But as well as having a relative advantage, the innovation benefits from being compatible with what the beneficiary currently uses.

Compatibility

We all come with baggage. Experiences, knowledge, familiarity with our ways of working. An innovation that is compatible with what we do now will be adopted quicker than one that does not.

the degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

The classic example is why we use the QWERTY keyboard on computers. On typewriters, such a keyboard layout acts to slow down typists to minimise the letter hammers jamming. We don’t have this problem on computers, so no need to use a QWERTY layout. However, it was a shrewd move to. It is familiar. And, on introducing computers to the market, we have an already-available pool of people that can use them.

I think we can broaden this concept nowadays to leverage what beneficiaries are used to in other markets/industries. So not just a computer keyboard replacing a typewriter. But, for example, the use of QR codes from travel industry into finance applications.

Complexity

The perceived attribute of complexity is fairly obvious. The more complicated something is, the steeper the learning curve. And therefore the harder it is to get people to adopt. So it is advantageous to minimise the complexity.

the degree to which an innovation is perceived as relatively difficult to understand and use

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

Complexity feeds into resistance as it increases the perceived risks of the innovation to the beneficiary. One approach to address complexity, if you can’t take it away, is trialability.

Trialability

Allowing adopters to trial an innovation is a way to increase the speed of adoption. It lowers uncertainty and allows for learning by doing.

the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

We are all familiar with this in marketing approaches. Free samples of goods, for example. Or freemium software (use a limited version of a service for free, pay for full functionality). Or charging monthly fees for a service instead of large upfront costs.

A downside could be that the adopters identify undesirable aspects of the innovation that outweigh advantages. However, if the innovator can react to address those findings, there are benefits all round.

And finally, the last perceived attribute is observability.

Observability

The easier it is for others to see the innovation in action (or that others are using it), the quicker it is likely to be adopted by others.

the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others

Rogers (2003) – Diffusion of Innovation

Apple’s iPod is an oft-quoted example here. Since it spent most of its time living in people’s pockets, it was hard for others to observe it was being used. Apple’s solution was to provide white coloured headphones. These were very uncommon at the time. But, even today, if you see someone going past with white headphones in their ears, you knew they are using an Apple product.

You can find the details in my article “Innovation Resistance“.

In short, we need to minimise physical, economic, functional and social risks. Am I going to be harmed using the innovation? Is there a chance I can be financially out of pocket – remember the Betamax vs VHS wars? Electric cars are fantastic, but if I mainly drive long distance, then I currently have a functional risk. And remember the social risks associated with the first edition of Google Glass?

Secondly, we live comfortably in a set of traditions and norms. Most innovations are going to challenge those. The greater the difference, the higher the likelihood of push-back. Similarly, any innovation that goes against existing usage patterns, or that cannot support existing usage patterns will likely face challenges.

Finally, we all have perceived images of how things are and should be. Could Japanese companies make top-quality motorcycles when they first established in the US? The perceived image initially was no.

Next we have the promotion efforts of any change agents.

The extent of Change Agent’s promotion Efforts

The efforts of change agent are, I believe, different depending on the innovation-decision. So are the types of change agent.

Change agents efforts in an optional innovation-decision

If we take an optional innovation-decision, then the change agent is initially the innovator’s messaging to each adopter type. As time progresses, the change comes from peers that are adopting. This reflects Bass’ view that there are initially innovators followed by imitators. We might see certain people in the social network as critical drivers of change through their actions – influencers, you might say. Targetting them could help with innovation adoption.

Change agents efforts in a collective innovation-decision

A collective innovation-decision starts to move towards more formal change management needs. The group needs to identify why they need to make a change (adopt something new). It might be an existing group looking for something new. Or it might be that a new group emerges, driven by the need to find something. Either way, they need to legitimise their search, make a decision and action the change. Rogers and Shoemaker (1971) identified the approach as stimulation, initiation, legitimation, decision and action.

Change agents efforts in an authority innovation-decision

In an authority innovation-decision – such as one taken due to legal/regulatory decision or by a senior manager in an organisation – we move to the realm of formal change management.

Kotter’s 8 accelerators of change (you may have previously seen called 8 steps of change) is my recommended approach.

Last but not least are the fourth and fifth aspects, the communication channels and nature of the social system.

Communication channels & Nature of Social System

The rate of adoption is, unsurprisingly, related to the rate that knowledge of the innovation spreads. And that in turn relates to

to be related to two factors that relate to diffusion. First there are the communication channels in place including network topology (here); type of messaging (16% rule)

One thing Rogers does not explicitly tackle, though we have included in our update adoption decision step is innovation resistance.

Minimising Innovation Resistance

As we’ve already seen, removing innovation resistance is the path to an adoption decision. And we’ve seen it is a scale between postponement, rejection and objection. Over in my article on resistance I go into detail on this. But the main point is we can identify a series of attributes that lead to the various resistances. Therefore, we should include them in our factors for adoption speed.

Multi-sided platforms

Adoption of multi-sided platforms raises interesting aspects. I’m talking about things like Uber or Air B’nB etc. Where there are two or more distinct groups that need to adopt. And adoption in one group is somewhat dependent on adoption by the other group. If there are not enough travellers adopting, it is less interesting for car drivers to adopt. Similarly, if there are not enough cars on Uber platform, there is little incentive for travellers to adopt.

The innovator needs to look at their solution through these different groups. First and foremost, what value is the innovation for both groups? Has that offering sufficient proposed value for each group (see “What is value?“).

But there is limited research presently on adoption and dissemination of multi-sided platforms.

Wrapping Up

Innovation adoption is one of the classic aspects/theory of innovation. I’ve tweaked it slightly to address innovation resistance – which is key to minimise for successful innovation adoption. As well as put the adoption decision step in the context of job theory.