The Big Picture…

What is value? I would wager your answer is similar to Golub & Henry’s:

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it

“Market strategy and the price-value model” Golub, H. and Henry, J.

But such a view of value restricts our ability to innovate and grow. Our focus is on the point of sale, where value-in-exchange happens. And that leaves us short-sighted (as Levitt famously said) to what the customer is really trying to achieve. Our innovation efforts end up in the “add another razor-blade syndrome”. Additionally, we are ignorant about what the customer does, and their success or otherwise, post sale. Giving us missed opportunities for growth.

The truth is that value is more complicated than price paid. In fact, price has nothing to do with value.

An improved view of value

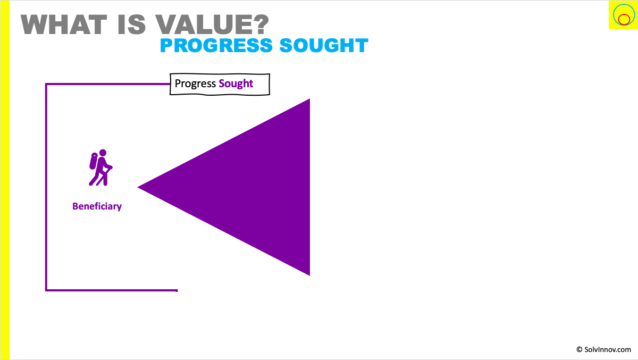

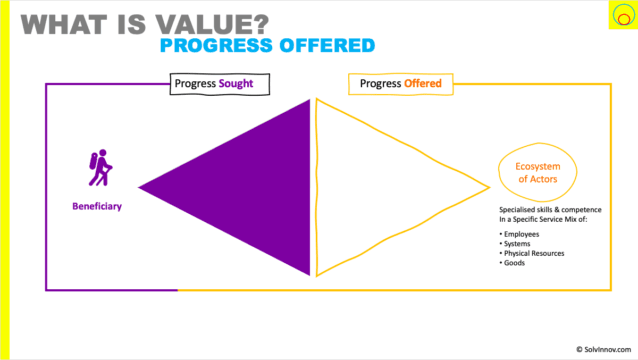

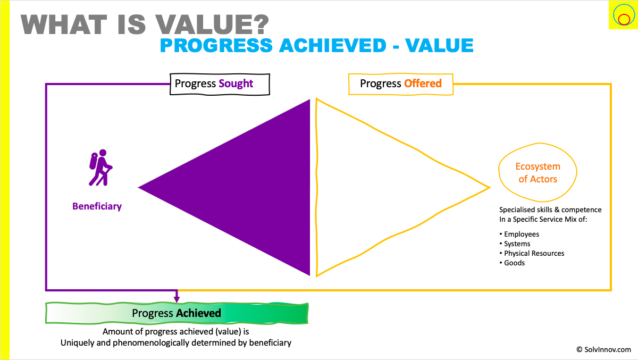

We can define value as being related to progress – sought, offered and achieved.

Let me explain:

- beneficiaries are seeking to make progress in various aspects of their life – progress sought.

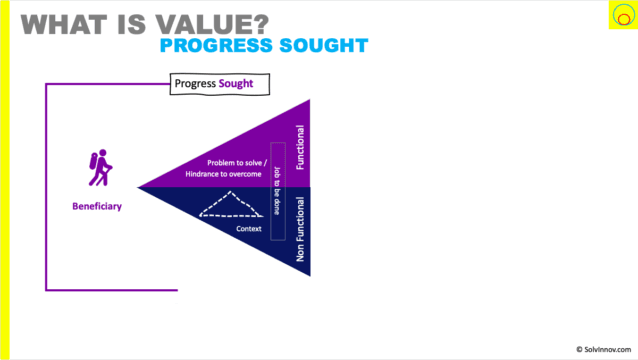

- progress itself consists of:

- functional

- non-functional – adverbs such as safer, quicker; and

- context

- a variety of ecosystems form with the purpose of offering value propositions to help beneficiaries make progress – progress offered. And this progress offered could match, be less, or be more than progress sought.

A beneficiary evaluates progress offered against what they are seeking. And, once engaging in a service, they continually determine the amount of progress they are achieving. They do so again once the service is complete. This is our measure of value – the amount of progress achieved.

Implications

There are many implications that fall out of this improved view of value. Not least how value is created (and can be co-destructed) and what price means (as it no longer equal to value).

Progress offered is expressed as a value proposition. And Enterprises are enabling systems for potential value co-creation. Enterprises need to constantly update their value proposition(s) in reaction to evolving progress sought by beneficiaries. That evolving progress sought explains trends, fads etc.

Innovation nicely evolves into the act of creating new value propositions offering to help beneficiaries make functional and non-functional progress better than they currently can.

Progress offered can be over-offered or under-offered. This view of value, consisting of both functional and non-functional progress, underpins Christensen’s Job-to-be-done theory. And the concept of progress sought and offered underpins Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation theory.

The Idea

We have a problem with innovation. And its root is in how we define value. Heavily paraphrasing, most definitions of innovation are based around creating something that adds value. But our common definitions of value does us a disservice when it comes to innovation and growth.

What is this usual view of value I claim we have? Let’s explore.

What is value – Our usual view of what is value

I would wager that you think of value in the same way as Golub & Henry do in their “Market strategy and the price-value model” paper. That is to say:

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it

“Market strategy and the price-value model” Golub, H. and Henry, J.

Even our language sees value this way. Here’s Merriam-Webster’s dictionary definition:

1: the monetary worth of something

Merriam-Webster

2: a fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged

3: relative worth, utility, or importance

4: something (such as a principle or quality) intrinsically valuable or desirable

And management consultants will tell you similar. McKinsey, for example, tell us in “A business is a value delivery system“:

Customers base their buying decisions on two criteria: the benefits of a particular product or service and its price. The benefits can be reduced to a single number: the most the customer would be willing to pay for that product or service. That number, minus the price, represents the product’s value to the customer

“A business is a value delivery system” Lanning, M. and Michaels, E.

Simply put, the higher the price we can achieve the more value we perceive there is. Value creation is seen as performed by the manufacturer. And there is a value-in-exchange moment – where a customer hands over money in order to own the value (see my article on how value is created for more details)

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it

“Market strategy and the price-value model” Golub, H. and Henry, J.

In such a view, something more expensive has more embedded value than a cheaper option.

Why is this problematic?

For a start, this view of value takes no account of whether the product we have exchanged cash for has actually done what we bought it for. And, as part of the same issue, it is the manufacturers that are setting the price, i.e. saying how valuable something is.

Now, supply and demand, you could argue, will eventually bring the price to reflect the value customers are getting. And that is often true. But my main issue is the value-in-exchange nature has two (big) implications:

- We risk limiting our innovation space

- We don’t see past the point of sale

Both of these points affect the effectiveness of our innovation efforts

Limiting our innovation space

Levitt’s classic “Marketing Myopia” tells us all about limiting our innovation space. Focussing purely on value-in-exchange makes it challenging for us to take a step back. Incremental innovation, at best, becomes our default mode. We’re unable to think about business model or radical innovations. Levitt references how American railroad went out of business by believing they were in the railroad business rather than transport business. And so missed the opportunity of air transport.

But its interesting to note Christensen, Cook and Hall note in “Marketing Malpractice: The Cause and the Cure“:

The great Harvard marketing professor Theodore Levitt used to tell his students, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” Every marketer we know agrees with Levitt’s insight. Yet these same people segment their markets by type of drill and by price point; they measure market share of drills, not holes; and they benchmark the features and functions of their drill, not their hole, against those of rivals.

“Marketing Malpractice: The Cause and the Cure” Christensen, Cook & Hall (2005).

And here we see a further impact of the value-in-exchange thinking – an internal focus develops. It leads us to focus on product attributes – we see adding yet another razor blade as beneficial innovation.

We need to think more about what the end-user is trying to achieve. That is to say what is value to them, not what is value to a manufacturer.

Not engaging past point of sale

Once we’ve made a sale, the pressure is on to make the next sale. We have little time to engage the consumer/customer does with our product. Or to find out if the customer has achieved the value they were expecting. And we leave opportunities to help customers renew value – through fixing, reselling and/or recycling or other aspects of the circular economy.

The solution, I propose, is to improve our definition of value. And from that flows an improved and actionable definition of innovation.

The proposed improvement to what is value

To improve innovation and growth, we need an improved view of value. And we get that from applying a service-dominant logic lens. Here we find a relational view. Where everything is a service. And that value created in use.

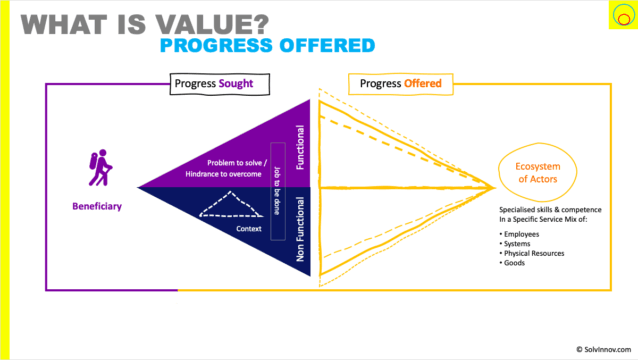

To me, the logical conclusion of service-dominant logic lens is that beneficiaries – those looking to engage a service – are seeking to make some progress in their life. We can call this the progress sought. And there are a variety of enterprises who establish themselves offering to help those beneficiaries make that progress. They do so using specific combinations of the service mix – employees, goods, physical resources, and systems – a value proposition, These are the progress offered.

Once a beneficiary decides to engage with a value proposition they integrate their resources with those of the ecosystem in an attempt to make the progress they are seeking. We can see this progress view of value in Figure 1.

This thinking comes from applying a service-dominant logic lens to the world. This leads us to understand that making progress is the only thing that is of value to the beneficiary of a service (and that everything is a service – goods are a distribution mechanism for service).

Making Progress is valuable

We need to move away from equating attributes with value. Since we tend to turn attributes into prices. And that leads us down the path of value-in-exchange.

Instead, we’ll make three observations. Firstly, beneficiaries are trying to make progress in various aspects of their life. We’ll call any particular aspect a beneficiary is trying to make progress in as the progress sought.

Secondly, enterprises form – often as an ecosystem – with the aim of offering to help beneficiaries in making progress . And the ecosystem offers specialised skills and competencies captured in a particular service mix. The offer is presented in the form of a value proposition (adhering to the service-dominant logic premise that ecosystems can only offer value).

And, finally, we observe that making progress is what has value to a beneficiary. The more progress they can make the more valuable the value proposition.

The beneficiary determines how much progress they are likely to make with a particular value proposition. And they continuously review how much progress they are making during the duration of the service. This aligns with the service-dominant premise that value is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary. And, importantly, value is now created in us (value-in-use is the terminology). Which means we need to think relationally, before, during and after service.

But the above is a rather simplistic view of value. Let’s look deeper into what progress sought, offered and achieved means in practice.

What is progress sought?

When we see value as a measure of progress achieved (potential and actual), we are forced to better understand what progress beneficiaries are trying to make in the first place. And that encourages us to avoid Levitt’s myopia. Since we (should) abstract from current solutions.

And, it turns out that progress sought comes in three flavours:

- Functional progress

- Non-functional progress – for example safely, quick, makes me feel good, etc

- Non-functional progress: context – often there is a context to the progress the beneficiary is trying to make

Let’s look at these types of progress.

Functional progress

Functional progress is the most obvious and tangible progress sought. This is the problem that the beneficiary needs solving. Or the hindrance the are trying to overcome.

For example, a functional progress I might seek is to have a face free of facial hair. This is more abstract that a potential alternative you may think of: “I want to shave”. It neatly captures the progress I want to make, without tying up to thoughts of solutions.

On it’s own, functional progress is the minimum to define innovation space. It is less myopic than you may previously have started from. For example, you could easily go ideating how to have a face free of facial hair.

But if we can observe and capture the non-functional progress a beneficiary is usually seeking, then we get a deeper insight into what the beneficiary finds of value.

Non-functional progress

Non-functional progress relates to progress that is can best be identified as feelings and context. Context we will cover next; but feeling wise, we could say in our facial hair removal example that the non-functional progress is: safely and quickly.

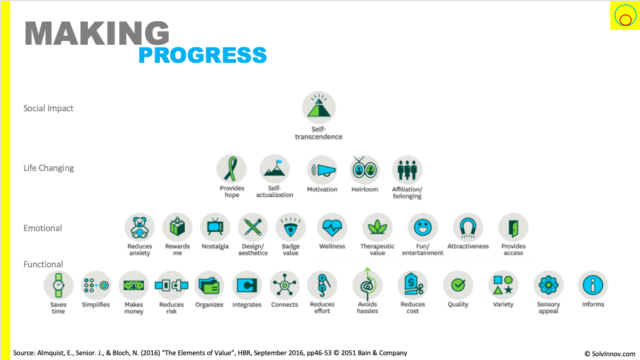

In the wider literature, Lindic and da Silva, for example, analysed Amazon’s customer innovations (“Value proposition as a catalyst for a customer focused innovation“). They identified those innovations revolved around offering improvements in:

- performance

- ease of use

- reliability

- flexibility

- affectivity

And Almquist et al’s “The Elements of Value” identify 30 elements of value. Which they place in a hierarchy: functional, emotional, life changing and social impact. Somewhat reminiscent of Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs.

I personally would rename the “functional” layer to avoid clashing with my idea of functional progress. And perhaps I would remove a couple of the elements as they are more functional progress aspects (such as organises, connects and integrates). But this hierarchy is a useful reference to explore progress sought against (and potential progress offered).

Non-functional progress – context

The third aspect of progress is context. It is part of non functional progress and describes the context of the progress sought.

Jobs To Be Done Theory

Christensen’s job to be done theory, described in “Competing against Luck” requires all three aspects of progress to be considered. That is to say, the functional progress, non-functional progress, and the context.

Mandated Progress

One thing to reflect on is that there might be progress to be made that is mandated by a party that is not the beneficiary. Typically these will come from regulatory bodies. And this progress may be at odds with, or restricts, the progress the beneficiary is seeking to make.

So, that’s progress sought. Let’s look at progress offered.

What is progress offered?

On the other side of the coin is progress offered. This is where one or more ecosystems (with a lead enterprise) form, offering to help beneficiaries make the progress they are seeking.

The ecosystem offers specialised skills and competences that potentially can help the beneficiary make progress if used. These skills and competencies are captured in a specific service mix. Which comprises some mix of employees, systems and physical resources, and goods. Where we see goods as a distribution mechanism for service. And are typically used in acts of self-service (see service-service continuum).

In line with service-dominant logic, the ecosystem can only offer a value proposition. It can’t determine value (the price it sets for engaging with its service mix is not a proxy for value). So we must become more relational in order to determine, support, and increase value offered and achieved.

To maximise progress offered, we have to first know our generic beneficiaries well. And secondly tailor our offering as best we can. The individual beneficiary likely has many value propositions to chose from. Including the do nothing (or wait until another time) proposition.

You might think that ecosystems would aim for an air-tight match between progress offered and progress sought. But, there are occasions where they may chose to either over or under offer.

Over/Under-offering

Porter’s generic strategies frames most examples of Over and under-offering progress that could be achieved.

Over offering is a means of differentiating. But also, you may have spotted progress being sought that the beneficiary is not aware of.

Under-offering is a means of driving a cost-based strategy. After identifying progress sought, you identify which progress is less important to the beneficiary and determine if you need to offer it. Less progress offered means less ecosystem effort in the service mix. Which in turn is reflected in lower price to the beneficiary (caution: make sure you read about price/value/effort to fully understand this and don’t see price as a proxy for value)

Disruptive innovation – deliberate under-offering progress

Disruptive innovation is a special case of under-offering progress. And perhaps the most misunderstood/misused term in innovation.

Blue Ocean Strategy

Are we offering the beneficiary the non-functional progress of saving time, avoiding hassles, and reducing costs, like Electrolux do with their vacuuming as a service.

We can use such a list when innovating. And it ties to Blue Ocean Strategy’s value canvas. Take you existing offering and see which elements of value can you increase, decrease, add or delete. And from a strict Blue Ocean Strategy view, you should do that from the perspective of your non-customers in order to find a blue ocean where your competitors are not.

What is Value? Progress Achieved.

Wrapping up

Innovation can simply be seen as offering to help a beneficiary make progress they are seeking in a better way than they currently can. Which by implication offers more value to the be created.

Old text below – in case reusable above

Enticing, Enabling and Enriching

In “Brand Admiration: Building a business people love“, we get a broader insight into what we can call non-functional aspects of value propositions. Whilst the research is based on brands, brands also represent the value proposition. They identify that people love brands that Entice, Enable and Enrich them. We can say that enable matches our view of functional progress.

From Eisingerich’s – one of the authors – article we see that customers:

“1. find value in brands that enable them. Such brands solve customers’ problems. They remove barriers, eliminate frustrations, assuage anxieties, and reduce fear. They provide peace of mind. With the brand as a solution, customers feel empowered to take on challenges in their personal and professional lives.

2. seek benefits that entice them. Enticement benefits stimulate customers’ minds, their senses, and their hearts. They replace work with play, lack of pleasure with gratification, boredom with excitement, and sadness with feelings of warmth.

3. seek benefits that enrich them and their sense of who they are as people.Customers want to feel as if they are good people who are doing good things in the world. They want to act in ways that are consistent with their beliefs and hopes; to feel as if they’re part of a group in which others accept and respect them; to feel proud of their identities and where they came from.”

Whilst this helps open our eyes to different aspects of making progress, it is still a little abstract.

Adam, I really like where you are going with this. Fundamentally you have a toolkit in the 30 items that enable value gap analysis, value creation proposals, value measurement and value reporting as an element of transformational methodologies. They link directly to core purpose when the 30 are equated/mapped against that purpose, and you have the capacity to prioritise value in a transformative journey that keeps the transformation aligned to the core purpose. It is the antithesis of the ‘shoddy’ innovation that results in the vast majority of transformation failures (which all to often values features and vision over purpose and compatibility of culture/alignment to mission. (Apologies – so much management consulting bull in one sentence)).

Have you a measurement methodology in mind?

Bingo Elliot. Pretty much my thoughts when starting this article (even if I have hit publish a little too early!). I want to look at the 30 Almquists items to see if I agree, but they are strong contenders.

Measurement is going to be tough, I feel. Key will be that needed closeness to beneficiaries, both in determining your value proposition (to minimise that shoddy innovation) and interestingly seeing what those beneficiaries actually do and where they create value!

To be honest, it feels like this is the sort of thing that cries out for a modified Balanced Scorecard. You have up to 30 factors that have varying impact on the service consumer, depending on the consumer’s own perspective. Value relates to Fn(Factor(Priority*Weight*Perceived Outcome)) for each factor. The relationship between the factors is important to the consumer (so probably a preceding activity by them to determine) and therefore enables definition of the modifier. If this is mapped against an open index (rather than absolute scale) then the value of the service can be constantly enumerated despite any ongoing transition caused by the maturity/impact of the service on its context. (i.e. treat it like a FTSE index with regular measurement, instead of trying to get an absolute value against a perceived target – you are probably well aware that I am a huge advocate of this approach to measurement since it tends to open the door to analysis rather than shut it down in the way that absolute values do.)

I’m starting to think the measurement question leads to an observation not yet surfaced in service-dominant logic (at least that I have seen).

The amount of value co-created has to be related to the amount of functional & non-functional progress achieved by the beneficiary. The beneficiaries determine that. And not all beneficiaries will make the same determination. And would they do that determination in our presence? Maybe for pure service; probably not for pure goods (even though for me those are frozen services that have been transported). So, that is going to be difficult to measure.

Like with a lot of service-dominant logic there’s a wider insight rather than an observation that the goods-dominant way is wrong…

If determination of value takes place away from you, and you don’t have the means to follow up, then the price paid and/or number of sales are proxies (or weak?) indicators of progress made by beneficiaries.

1) If not enough beneficiaries make enough progress, then, through innovation diffusion?, the number of sales will be low; and vice versa.

2) Price paid effectively equates to number of service credits a beneficiary is prepared to swap to make the progress offered. As a group of beneficiaries there must be a max level at which they need to offer their service to gain credits they then use to make this progress.

We do loop back to a foundational premise of service-dominant logic: the ideal situation is we need to be beneficiary oriented and relational. To be able to ask/observe the amount of progress beneficiaries make and how much effort they are prepared to make to gain service credits. Where we can’t (or didn’t observe that we previously needed to) then number of sales and price paid become proxies for that – good or bad, strong or weak, I don’t now, yet….

” the ideal situation is we need to be beneficiary oriented and relational” – I like to imagine that there is a sleight of hand that can be played here. Returning to the concept of a measurement index, when we imagine the FTSE we see that it is an abstraction of a highly complex array of service-centric measurement – the services are related to actions upon the values contained within the index and the companies that constitute it. This only works because of its abstract nature – The measurement has become a thing separate to that which it is measuring. If your measurement of service is in fact a thing in and of its own doing then the concept of value becomes a) truly related directly to the consumer (whatever the pattern of factors they employ) and b) abstracted to the point where all consumers can be interrelated despite having different definitions of value.

that abstraction is probably “price paid” and/or “volume sold”. Initially I was tempted to write they were wrong measurements, but eventually settled on them being aspects that are visible in the absence of better understanding. They do kind of act like an abstraction. If we are selling a lot, or at high price, then the offering must be helping beneficiaries make progress. And given the fickleness of beneficiaries, it’s hard (?) to say which types of progress, but on aggregate there must be enough . Which is a good “conclusion” as they are clearly used today so this view of value needs to explain why price and volume are currently good enough indicators.

Do we need to do better? I suspect for some service no, for others yes.

Particularly when we think that the value proposition needs to appeal to as wide an audience as possible – in most cases I suspect you need volume to be viable. But, once a beneficiary picks your proposition, then customisation to improve the offering (before starting, and during) can be a benefit to the beneficiary. Hence the need for relational aspect. The beneficiary oriented is the need to remember you create nothing of value, value only comes from it being useful to the beneficiary)

Interesting stuff to think through, and thanks for thoughts