The Big Picture…

We traditionally classify economies based on their main output. For example, our education – steeped in goods-dominant logic – will tell us there are agricultural, goods, and service economies. And that we progress and mature through them in that order. Our key indicator of era is the type of output that is exchanged for value.

But, in service-dominant logic, we recognise service as the fundamental basis of exchange. Although that exchange might be masked by indirect exchange.

Therefore, as we see everything is a service, we see all economies as service economies.

In such a service economies view, economic eras are those periods when a particular competence is most favoured. And that is determined uniquely and phenomenologically by the beneficiaries.

If we recall that service is the application of competences – skills and resources – by one entity for another entity’s, or its own, benefit. The agricultural era, for example, we see as one where competence in cultivation is predominant.

Implications

In itself, this is a subtle observation – rather than look at outputs, we look at how those outputs happen (application of competences), and find that all economies should be considered as service economies.

However, it leads us to noting that trying to find growth by continuing to apply goods-dominant logic is not optimal. We need to look at growth (and innovation), enterprises and economies through service-dominant logic.

Additionally, we get to understand the oft talked about “shift to the service economy“. And we see the shift is really one of competences that are valued. A shift towards the competence of resource integration. This is likely be due to the reasons listed in my article: economic, user behaviour, asset and/or data.

The Idea

If we agree with the 1st foundational premise of service-dominant logic – that service is the fundamental basis of exchange – then we naturally arrive at the 5th foundational premise:

All economies are service economies.

Vargo & Lush (2016) – Foundational Premise #5

It’s hard not to. Since if every exchange is vased on service then everything in the economy is a service; hence the economy is a service economy.

However, we traditionally are taught to classify economies based on outputs. And we draw conclusions on economic maturity by observing shifts over time. Typically we see the following eras: agricultural, goods and services.

But this is a classification with roots in goods-dominant logic. Where we focus on outputs and see value as being exchanged. We value the grain, for example, more than the seeds in agricultural economy. Or in the goods economy we see the manufacture as embedding value through their production process.

Under a service-dominant logic we focus on how the outcome comes about rather than the outcome itself. And that is that an entity applies its competence for the benefit of another entity, or itself. This is one of the definitions of service.

Let’s take the journey to see why and how this world of all economies are service economies fits. And we’ll start by looking at the classic way of defining economic eras.

Economies viewed in a traditional way

Even those of us with a small appreciation of economics will remember learning about agricultural economies and the industrial revolution. And we’ll have some notion that goods economy is somehow more mature/better than agricultural; and similarly a service economy is an evolutionary improvement to the sweatshops of factories.

Figure 1, from Chesbrough’s book “Open Innovation“, nicely represents our traditional thinking of economic eras.

Here we see that the US economy has developed, we would say, from mostly agricultural-based in the 1800s. Through to a prediction that it will be mostly services based in 2050 with a little percentage of agriculture.

That is to say it will shift from mostly producing grain, for example, through manufacturing farm tools, to making cars, to providing rental cars at airports, to Uber and beyond.

Of course, we are talking percentages here, so this doesn’t show that the agricultural aspect of the US economy will be financially small, just as a percentage, it will be small. Nor does it lead us (erroneously, as we’ll see) to equate an agricultural economy with less developed times/areas.

What we are doing is framing each era on the type of output. That is to say, what is being exchanged. Let’s now think of this differently – through service-dominant logic.

Let’s think differently

Vargo and Lush encourage us to look at things not as the outcomes, but as the actions used to get the outcome:

each era ‘might be better viewed as macro specializations, each characterized by the expansion and refinement of some particular type of competence that could be exchanged’

Vargo & Lush (2004)

That is to say, we should consider the entire economy as service-based. And, there are periods where certain competences are favoured. When society starts, or circumstances allow us, to view a different competence as beneficial, a shift to another era could be starting.

We can re-frame the typical eras from outputs to these competence:

- Cultivation

- Mass production and management

- Resource Integration (to get a job done)

And when we do so, we arrive at the comparison in Figure 3.

The competences which are dominant are those that beneficiaries uniquely and phenomenologically determine as being beneficial.

Rather than revolution, this is an evolution in thinking. As we will see below, where we look at each era and shifts, the service view is always there, just often not exposed.

The agricultural era

When an economy’s output is predominately food- and live-stock based, we classify it as an agricultural economy. We recognise few goods or service. However, in our service based view, we recognise that there is skill required to cultivate food- and live-stock. And it is really from here that roots of goods- and service-dominant logics diverge.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (“A Theory of Human Motivation” (1943)) places physiological needs – eating, drinking, etc- at the base. And the most basic competence we can have is the ability to forage for food. And to know the difference between edible and poisonous food. So we start off talking in terms of service – applying competence for the benefit of ourselves. And when we form groups, for others.

Soon we gain competences in cultivation. Reducing risks of not finding food. And foraging turns to subsistence farming. Which often transforms to managing to create surplus.

Farmers begin to specialise – one begins focussing on cultivating grain, for example, since their land is good for that; another with poorer growing land perhaps focusses on husbandry of pigs. But, the pig farmer still needs grain to feed their animals. And the grain farmer might enjoy a pig to feed their family.

And so the two farmers now look to exchange…something.

What is exchanged?

And this is the crux of the difference between goods- and service-dominant logic.

Do the farmers exchange something of value – an output. Or do they exchange the service – application of their now specialised competence – which helps create that output.

Actually, neither view is fundamentally wrong. The way we are taught economics, and how we casually see the world, would point us to the output based view (goods dominant logic). Mainly as we are comfortable seeing cash underpinning exchanges. This view, though, has limitations.

But, we can equally see a world where both farmers are exchanging their specialised competences for the benefit of each other. One eats the pig that was raised by the other farmer’s husbandry skills. And the other can raise the pig due to the grain farmer’s cultivation skills.

This is a case of I do something for you and you do something for me in return. And service dominant logic sees everything works this way. Though we know that some service is more detailed than another – raising one pig is more effort than cultivating one ear of grain. And that there may be indirect exchange of service. So we can think of cash as a form of service credit.

Shifting

Economists see that agricultural economies give way to goods economies as, due to growth, less proportion of income is spent on food. This is Engel’s law.

As a family’s income grows, then the proportion of income spent on food reduces (even if the absolute value increases)

Engel’s curve/law (1857)

And so more money is available to spend on other things.

In our service-dominant logic world we can say that it is no longer a zero-based game between cultivation service we provide and cultivation service we get in return. We end up with some spare service credits to use. And given the indirect exchange, we are not usually restricted on where we use those credits.

The Lewis (dual-sector) model explains how labour transitions between the capitalist and subsistence sectors. And it explains growth in a “developing economy”. This is a little out of my comfort/knowledge zone, so I won’t describe or discuss. But, suffice to say, we get a growing industrial sector. Perhaps even explosive growth if we look at the UK’s industrial revolution.

The goods era

What do we do with our spare service credits? We exchange them for more service. But we have already exchanged for sufficient cultivation service. We’re comfortable on Maslow’s hierarchy. So we tend to exchange for non cultivation service.

In traditional terms, we have spare cash, which we predominantly use to start buying goods.

We saw, during the western world’s goods era, the rise of science and a desire to understand economics. This means most of our theories are based on observations of manufacturing. And this is exactly what goods dominant logic is. Value is based on output and is embedded through the manufacturing process. Making output more valuable than inputs.

Back in 1776’s ‘Wealth of Nations‘, for example, Adam Smith viewed manufactured items (goods) as wealth-generating. Services, he argued, could not contribute to wealth generation. And this thinking really underpins the goods vs services theme we see time and time again. Goods are good, services are bad (inconsistent, require involvement, are inseparable, you cannot create an inventory etc). But we find this is not true.

As goods become important we seek ways to make their production more efficient (cheaper) and consistent (quality). And that gives an advantage to those that can manufacture at scale. Goods themselves start requiring other goods – machinery requires replacement parts; batteries are needed for electronic toys.

Goods are a service

And what do goods do? Well, they help us make functional and/or non-functional progress in some aspect of our life better than we could before. in service-dominant logic, goods are a distribution mechanism for service. That is to say, they freeze a service – application of competence for benefit of an entity – so it can be distributed elsewhere and unfrozen in use.

Farmers can buy a plough, or a better plough. That plough freezes the plough makers competence of knowing how to plough more efficiently, or safer, or…. It is transported to the farmer. And unfrozen each time the farmer (beneficiary) uses the plough. The plough helps the farmer make progress in their life better than they could before. An alternative, to help understand why goods are service, would be for the farmer to hire more people to plough.

Competence in the goods era

Making one item lovingly – the craft industry as we might be tempted to call it nowadays – requires a different skillset to mass production. As society starts to require more competent people with craft skills, society can either create more craft competence or start to value mass production. And with mass production competence comes a need for managerial competence.

So, the goods era is really one where mass production and management competencies are predominant.

The service era

Finally, an unescapable casual observation is of growth in the service economy over time. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was saying in 2000:

manufacturing [is] slipping to less than 20% of GDP and the role of services rising to more than 70% in some OECD countries

OECD, 2000

Later still, in 2017, the UK reported its economy as already being 79% service-based (products: 14%, agriculture: 1% and the remaining 6% was construction).

And, Deloitte’s 2018 article, “The services powerhouse: Increasingly vital to world economic growth” is a fascinating article to read. Not least in the way it talks about transition and goods/service eras.

So much so, that we talk of the shift to service economy. But by now you hopefully expect I will say there is no shift apart from in the competence we value.

And so it is. The “service economy” is one that values competence of resource integration to help make progress.

Shifting to resource integration competences

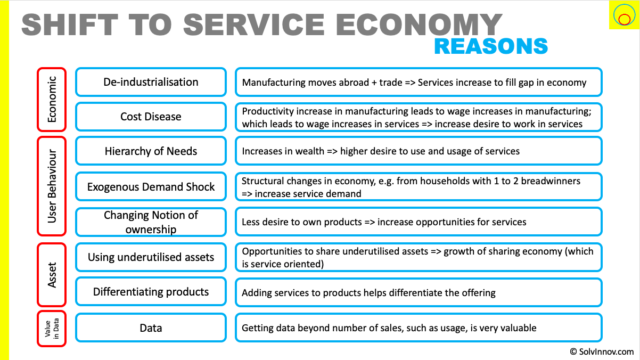

There are several reasons why society starts to favour resource integration competencies (service). I’ve broken them down into the four categories you can see in Figure 5: economic, user behaviour, asset, and leveraging of data.

I go into them in detail in my article “Service is eating the world – the shift to the service economy“. So I won’t repeat them here.

Era of Resource Integration Competence

And so we arrive at the era of applying and improving resource integration competencies. That is to say back to it being more obvious that it is service in action.

We see value propositions being offered. And resources are integrated (provider and customer) in order to take those value propositions and co-create value. In my article “Describing a service – to help discover innovations” I use Gallouj & Weinstein‘s model of service to explore this integration. Figure 6 shows this model, and intuitively, a service has a set of external characteristics. These are achieved by some combination of the customer, provider and goods/processes being integrated.

What about firms?

Under service-dominant logic we also believe that a firm acts as a service economy. That is to say that all firms are service firms. Additionally, all firms are internally service economies. Interactions between departments all follow service-dominant logic foundational principles.

Wrapping Up

So, as we see service as the fundamental basis of exchange, then we can derive that all economies are service economies. And as we know that service is the application of competence (skills and resources) for the benefit of an entity, or the entity itself, then all economies are economies where we apply competencies.

The concept of using plural for economy implies that the dominant competencies are different. And we saw that the old-school agriculture, goods and services economic eras can be thought of as economies where the following competencies are dominant:

- Cultivation

- Mass production and management

- Resource integration

And finally, we can say that shifts between economic eras are driven by society deciding that a new set of competencies are more beneficial than the current set. The “shift to service economy” is actually society favouring resource integration competencies over mass production and management.

Next Steps

There is a challenge with truly embracing that all economies are service economies and that service is the fundamental basis of exchange. And it comes from our casual observations of today. In service-dominant logic, we refer to it as “indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange“.