The Big Picture…

We really need the circular economy to work. An economy that, amongst other things, aims to minimise waste and pollution through reusing, sharing, refurbishing and recycling goods. Yet, only 9% of the economy is currently circular, and trends suggest this is decreasing.

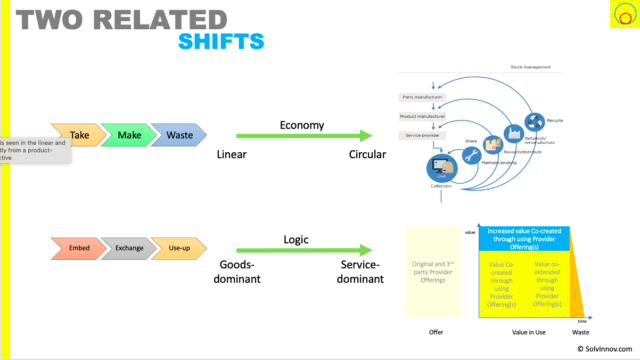

The Circular Economy is a move from the linear economy of take-make-waste to one that:

- designs out waste and pollution

- keeps products and materials in use

- regenerates natural systems

We do that by looking to maintain/prolong, reuse/redistribute, share, refurbish/remanufacture, or recycle goods.

To make such a circular economy operate effectively we have to

- build relationships with customers and look beyond the sale

- move from value-in-exchange thinking (where manufacturing embeds value and all focus is on the sale)

- create value together (co-create value)

- co-ordinate many actors to (repeatedly) achieve value

And those aspects are exactly what service-dominant logic thinking encompasses and promotes.

And the factors behind the “shift” to service economy can also support a circular economy thinking. But we have to be careful – a service-dominant logic economy can lead to more waste. We can easily create, for example, subscription models that encourage increased volume of throw-away goods.

Today’s world – it’s all about maximising value to exchange

Think of how we typically make and use goods today.

We take raw resources, make various component parts and assemble those parts into the finished goods. Across the supply chain, each supplier’s focus is on selling their output to the next link in the chain (we look on this as value-in-exchange). And, at each exchange, we believe the supplier’s output has more value than the input. That is to say, the supplier has embedded value.

A car, for example, is manufactured from parts, which are made from raw materials. We see the car as more valuable than the individual parts, i.e. the car manufacture has embedded value by assembling the car. And we see the parts as more valuable than the mined raw materials, i.e. the component part manufacturers have embedded their own value by making those parts from raw material. Finally, the supplier that takes the raw supplies out of the ground has embedded their own value to be exchanged for cash.

Eventually, someone sells the final product to the end customer – the final value-in-exchange transaction.

Now the customer has the product, they go about destroying, or using-up, all that embedded value. They wear down the car through repeated use, or they eat the cake that came in the nice box. And when the product has no value left, it is thrown away; and the supply chain again focusses its efforts to get the customer to buy a replacement product.

We typically refer to the above as goods-dominant logic – where logic just means the way we act, behave and observe the world.

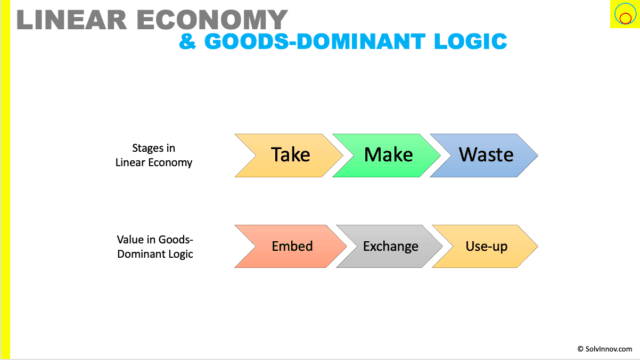

Goods-dominant Logic and Linear Economy

The takeaway here is that suppliers, under a goods-dominant logic lens, are rarely interested in what happens to their output. This has a parallel in the “take-make-waste” model of the Linear Economy.

If our focus remains purely on and stops at the point of exchange, then suppliers (the takers and makers) have little incentive to minimise waste, pollution, or that scarce resources are locked away.

Tomorrow’s (needed) world: The Circular Economy

One thing is for sure: we can’t continue with all the waste we generate in the linear economy. Firstly, it’s not environmentally friendly. Let’s just take the following, quite astonishing, fact:

total greenhouse gas emissions from textiles production, at 1.2 billion tonnes annually, are more than those of all international flights and maritime shipping combined

A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future – Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017)

Secondly, we have limited physical resources to take, and too high demand for those; a demand which is only increasing.

We need to find an alternative to the linear economy. An approach where, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation lists, we:

1. design out waste and pollution

2. keep products and materials in use

3. regenerate natural systems”

And it is those three principles that are used to define the Circular Economy.

You can see this definition of the circular economy in Figure 3. And we get to see why it is called circular.

There are two streams: renewables flow management, on the left, and stock management, on the right. I’ll concentrate on the stock management part – the right-hand side – in this article. And we can see there are four blue loops, covering:

- Maintain / Prolonging & Sharing

- Reuse / Redistribution

- Refurbish / Remanufacture

- Recycle

Where the intention is to keep within the inner loops before moving to the outer ones. For example, reuse is preferred over refurbishing and maintaining over reuse, etc.

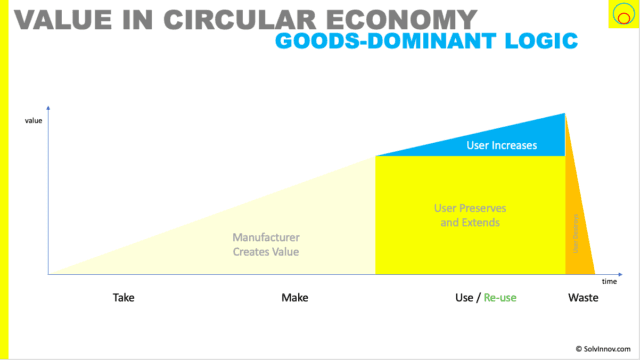

So what does the circular economy look like from a goods-dominant logic perspective?

The Circular Economy in Goods-dominant logic

Let’s explore what the Circular Economy using our predominant goods-dominant logic lens. First things first, manufacturers and suppliers are still seen as creating and embedding value. And that value is still seen as exchanged. So far, the same, as you can see in the left part of Figure 4.

Where we would observe differences is in the customer (or user) behaviour. Previously we see them as destroying / using-up value immediately. Now, they would attempt to:

- Preserve and extend previously embedded value – maintaining or reusing, for example; and

- Increase previously embedded value – such as through recycling or sharing.

Our observation is, though, that under goods-dominant logic it is the manufacturer that embeds value and the customer that then does something with that embedded value. In the linear economy, the simply use-up/destroy it. Now, in the circular economy, they try and preserve, extend and/or increase. There is still the divide of value-in-exchange. And there is no driver for manufacturers to enable the circular economy through design for re-use, recycling etc. The thinking of suppliers is always embedding value and making the next value exchange the largest exchange they can.

It is sobering to note that in 2019, only 9% of the world’s economy is currently seen as circular. And sadly, that trend appears to be decreasing.

Only 9% of the world economy is circular and according to the Circularity Gap Report 2019 the trend is negative

“The Nordic Market for Circular Economy – Attitudes, Behaviours and Business Opportunities” SB Insights (2019)

So what’s the idea?

Service-dominant logic, rather than goods-dominant logic, is key to understanding and super-charging the circular economy. Why? Well, it fundamentally removes the artificial divide created by the exchange of value in goods-dominant logic.

This is an evolution in thinking, not a revolution as you’ll find in my article journey “Making service-dominant logic more approachable“. Under service-dominant logic we see that value is:

- created during use rather than being embedded prior to exchange

- co-created by all the actors involved

- phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary (loosely: determined by the customer, based on their lived experience)

Having this different view of value naturally moves our thinking beyond the point of exchange.

Additionally, service-dominant logic refreshes some other beliefs we have, such as:

- service is not inferior to goods, service enable beneficiaries to make progress in some aspect of their life (see “Goods are good; service is bad – not quite“)

- goods – intangible objects, books, cars, furniture etc – are distribution mechanisms for service

- customers – are resources not targets and we need to think of them in the context of their own networks

What are the implications?

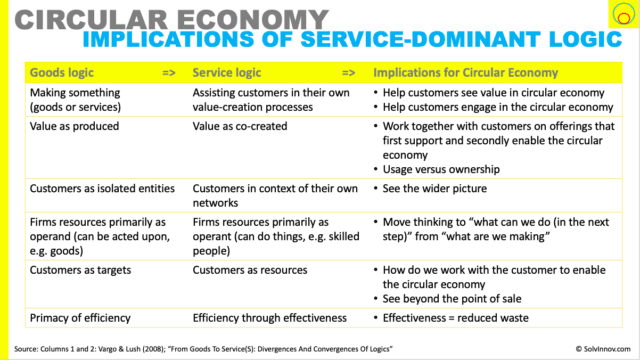

Let’s borrow and extend a table from Vargo & Lush’s “From Goods To Service(S): Divergences And Convergences Of Logics“) to see the implications of service-dominant logic on circular economy thinking.

The first two columns in Figure 5 come from the paper and show the managerial implications of goods- and service-dominant logic thinking. And I’ve added a third column showing implications of service-dominant logic for the circular economy.

In short, service-dominant logic requires manufacturers to help customers partake in the circular economy. It abstracts to a job to be done (helping beneficiary make progress) thinking as well as removing hindrances. It also means a move away from a purely build a good for maximum value exchange approach – the good is a way of transporting a service and value is co-created during use.

The logic also reflects that beneficiaries (generally end customers) need to see value in the circular economy. And, crucially, that value is phenomenologically determined by the customer. Which in essence means the same customer may value the circular economy differently for each situation they are in (even for the same goods).

Can we see any practical implementations of this? Yes, for sure.

Practical implementations of Service-Dominant Logic in Circular Economy

Over in my article “Service is eating the world” I look at various drivers in the shift of our economies appearing to become more service-based. In particular, three are relevant to our discussion here. Namely:

- Asset – differentiating the offering by adding services to the product

- User behaviour – the changing notion of ownership

- Asset – using under-utilised assets

We’ll look at the implications of those next with regards to the circular economy. As well as noting that the circular economy is inherently service-based itself.

Servitisation of goods

Service-dominant logic’s focus on the combination of value-in-use, only being able to offer value propositions and goods being transport mechanism for service enables a different way of thinking. It helps diminish marketing myopia by getting us to focus on offering a way of solving a job to be done and/or removing hindrances. This means our solution space is much wider than just selling a good.

Servitisation of goods is one way of achieving this, which is defined by Vandermerwe and Rada as “moving from the old and outdated focus on goods or services to integrated “bundles” or systems, as they are some- times referred to, with services in the lead role”. Two examples often quoted are Rolls Royce aeroplane engines and Schipol Airport lighting.

Rolls Royce – power by the hour

As an airline, you need reliable, safe and affordable thrust. And that comes from your engines. But, do you want to buy an engine, deal with maintenance, source spare parts, and eventually deal with decommissioning?

In goods-dominant logic, yes the engine supplier wants you to do that. They require a large capital payment for each engine to fund their R&D into the next engine they can sell you.

However, in service-dominant thinking, the engine manufacturer can sell you the service of available thrust instead. Or as Rolls Royce call it, power by the hour.

Now Rolls Royce takes care of the engine, the maintenance, the disposal at end of life etc. They are economically driven to minimise their costs. Which means looking beyond the moment of value-in-exchange and harnessing the circular economy.

They need to design their engines to be more re-usable, refurbish-able and recyclable. And they’ve installed sensors and use the power of data for their benefit – to pre-emptively schedule maintenance, for example. But that data can also be exploited for additional areas of value co-creation, such as reducing fuel consumption.

Schipol Airport Lighting by Philips

Another case in point is Philips, ENGIE and the lighting of Schipol airport’s terminal 2. Schipol no longer pays for bulbs, they pay for lighting (as a service).

As with Rolls Royce, this drives Philips to design easily repairable system that they can recycle and re-use at the end of the contract. The company that makes lightbulb. And the ENGIE company has implemented a control system that immediately picks up on any bulb failure.

Schipol pay a single monthly fee and the providers have the incentive to lower their costs (through harnessing the circular economy)

The Sharing Economy

The second two drivers in the “shift” to the service economy – using underutilised assets and the changing notion of ownership – bring us to the sharing economy.

Did you know in the UK cars are parked (not in use) 96% of the time! And whilst we’re talking about cars, if you drive yours to work, then you’re probably leaving a parking space unused at home. JustPark will help you hire that out on an hourly basis.

And those are just two examples of many in the sharing economy! Here’s a snapshot of what was being shared in cities in 2017 (from a World Economic Forum report called “Collaboration in Cities: From Sharing to ‘Sharing Economy’“).

As a further reference, McKinsey looked at 28 industries and identified that 22 of them could benefit from adopting sharing. Although, they have a wider definition of sharing as “promoting the sharing of products or otherwise prolonging product lifespans through maintenance and design”

Circular Economy is Service based

And finally, I can’t help but see each loop of the circular economy as being a service.

Editing below…

What then if we look at the circular economy through a service-dominant logic lens?

The Circular Economy through the Service-dominant Logic lens

Taking these differences on-board, we arrive at Figure 8.

What are we seeing in Figure 8? Well, we can look at it as two parts. First, there are a set of value proposition offerings, that have no inbuilt value on their own. And second, there is value in use driven by the beneficiary’s behaviour.

The Offerings

On the left, of Figure 8 there is a range of value proposition offerings. One of these is the offering from where the tangible item enters into the circular economy. The other offerings will be those to recycle, maintain, reuse, refurbish etc.

We will find that it is perhaps the original actor that decides to make a range of offerings. Or it could be a range of actors making these propositions. Perhaps the original actor decides to make all the circular economy offerings. Or it could be one or more actors per offering type. What is needed is actors to work together in a network to enable each other. And the main responsibility is on the originating actor.

For these actors, there has to be a benefit to offer their propositions. And that comes in the form of their business model. OECD’s report “Business Models For The Circular Economy: Opportunities And Challenges For Policy” helpfully identifies 5 business models common in the circular economy:

- Circular Supply – replacing traditional material inputs with renewable, bio-based, recovered ones.

- Resource Recovery – produce secondary raw materials from waste

- Product Life Extension – extending lives of existing products

- Sharing – increase utilisation of existing products and assets

- Produce Service Sytems – provision of services rather than products. Ownership remains with supplier

The Beneficiary’s Behaviours

It is the beneficiaries that decide the value in the service-dominant logic. So it is they that select the value propositions in which they wish to partake. And they that decide if enough value is co-created to ensure the survivability of the provider(s).

In an ideal world, this beneficiary driven value determination will favour collections of offerings that maximise the circular economy. There would be a preference for initial offerings that maximised value from other offerings. For example, the mobile phone manufacturer that maximised reuse, maintenance, remanufacturing. Or the fast-fashion company that alleviated the guilt of high-velocity purchasing by collecting last week’s styles and recycling.

Sometimes we need external influences. Such as deposit schemes on plastic bottles to encourage recycling.

But there is organic growth in the service market – services are eating the world. And four of the reasons align with the business models above:

- Changing notion of ownership – sharing

- Using under-utilised assets – sharing

- Differentiating products – product service systems

- Value of data – subscription models

However, we need to be careful with the last model – subscription. If that involves distributing the service using tangible goods then it needs to consider how to recycle/remanufacture to avoid increasing waste.

Sniph, for example, is a subscription perfume service. Each month an 8ml glass vial of selected scent is mailed. To minimise waste, Sniph send a pre-paid envelope in which you can return 5 empty vials. In return you get an additional filled vial.

Wrapping Up

[to be written]

On page two you can find some examples of circular economy companies and approaches.