The Big Picture…

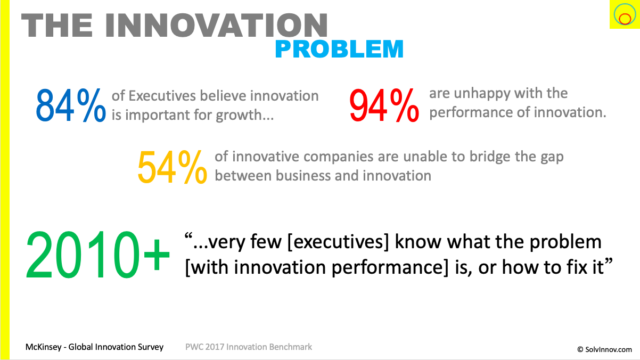

“94% of executives are unsatisfied with innovation performance”. Yet “84% see innovation as important to growth”! And “54% of companies struggle to bridge the gap between innovation and business”. Worse; “very few executives know what the problem is and how to fix it”!

This is the innovation problem.

What are the causes? Fundamentally we have forgotten Drucker’s insight: that “the firm has two, and only two activities: marketing and innovation”. Rather we drive for efficiencies and maximising sales prices. Innovation becomes something extra to do.

And, sadly, we turn to performing innovation theatre as we try being innovative. Weaving the words innovation and innovative into every corporate speech, advert and job description. Talking about changing culture to be more innovative. Running innovation calls to action, setting up innovation rooms and spaces. Yet our enterprises are not set up operationally to handle innovation nor do we attempt to change them.

Without realising it we have wrong notions of value. Thinking that we create it during the development/manufacturing process. And that we sell items that hold that value. The worst is our education system – sales, marketing, management, MBA – persists these myths.

And our basic innovation theory assumes all innovation is good. So just needs to be diffused and adopted. Not noticing that innovation can be resisted. Or that value can be co-destructed.

Implications

Innovation, on the whole, is broken. We can keep spending resources doing things the way we are now. And achieving the same results. Or we can find a better way…and that’s what I explore across this site (starting with understanding what value really is and seeing the world from a service (making progress) perspective).

The Idea

Innovation, as a buzzword, is everywhere. CEOs highlight innovation in corporate speeches. And so does marketing copy, which can’t stop using the word. Organisations perform grand-standing innovation activities (innovation theatre). We try internal, external and open innovation. And, seemingly, every job advert is looking for innovative people to fill innovative positions.

However, we are not making the difference we expect and need. And McKinsey’s found only 6% of executives are happy with innovation performance. This is a concern since our economies are becoming stagnant. And growth for companies is elusive.

In this article, I’ll explore what this problem is and why we have it.

OK, so what is this innovation problem?

Of the executives surveyed by McKinsey’s, 84% agreed that innovation is important to their growth strategy. However, only 6% of those executives are satisfied with innovation performance.

Think about that. 94% of executives are unsatisfied with innovation performance. Despite 84% of those same executives believing innovation is important for their organisations’ growth!

And it is not just McKinsey surfacing these challenges. PWC’s 2017 Innovation Benchmark found that 54% of the companies they surveyed were struggling to bridge the gap between business and innovation.

In fact, there are many reports and figures I could repeat and summarise indicating there is an innovation problem. But I think this blog post from Viima – 50+ statistics on innovation – does a great job.

And, what is worse, is that McKinsey’s survey uncovers that “very few [executives] know what the problem is, or how to fix it”.

The innovation problem: "very few executives know what the problem with innovation performance is, or how to fix it" according to McKinsey. Here are some insights… Tweet thisOur economies are stagnating and organisations are failing to find sources of growth. As Peter Drucker coined it: “innovate or die”. R.I.P. Blockbuster, Toys’R’Us, AOL, MySpace, Nokia and many more. And more concerningly: potentially you.

But why should we innovate?

Our innovation problem is only a problem if we agree that we need to innovate. So why should we innovate? It’s all about survivability and growth.

Because the purpose of a business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two – and only two – basic functions: marketing and innovation

Peter Drucker (1954) “The Practice of Management”

Over time, as you see in Figure 2, the revenue of an enterprise reduces if it does nothing. There are fewer customers wanting its ageing offerings. And at the same time competitors eat away market share. Sure, costs naturally reduce over time due to efficiencies. But cost reductions rarely cover revenue loss.

Even non-profit organisations, government institutes, etc follow similar paths. Although revenue may be called/seen as something else. And perhaps other, similar, metrics replace growth such as people helped, or area of land saved.

We should innovate, then, to reduce costs quicker and find growth. We look to enhance products. To introduce new products. And seek new customers and markets. And this is often to react to various market changes. Deloitte’s 2018 “Innovation in Europe” report highlights 88% of the 760 firms they interviewed planned to increase their innovation budgets over 2 years.

Drucker highlights seven sources of innovation that every manager should be monitoring all the time (in Innovation and Entrepreneurship):

- “The unexpected – what of your and competitors unexpected successes and failures can you capitalise upon?

- Incongruity – what are the unmet needs and wants of your customers?

- Process needs

- Changes in market/industry structure

- Demographic changes

- Changes in meaning and perception

- New knowledge”

Notice that I said, “we should innovate”. But we’ve just read that 94% of executives are unhappy with innovation efforts. What is going wrong?

So, why is Innovation not performing?

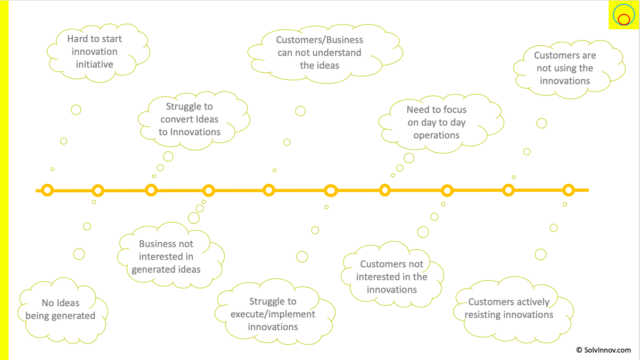

I believe there are many reasons innovation performance is not what we need it to be. And maybe you recognise one or more of the symptoms I show in Figure 3. These are the points I often hear these when people informally talk about innovation not working / not performing / failing.

You probably have similar and even additional points based on your own experience (would be great to hear about them in the comments).

But, why do we have these symptoms? Let’s dig into some of them, in no particular order.

We’ve forgotten what an enterprise is for

I’ve already touched on Drucker’s The Practice of Management observation that “a company has two, and only two, functions: marketing and innovation”.

It is not an obscure quote. And it gets taught in all management schools. Yet think of your own enterprise. Are you organised around marketing and innovation? Or are you organised around operational excellence and overhead reduction/minimisation? Are you managing through metrics that down emphasise innovation?

One reason for the innovation problem: enterprises aren't organised to fulfil Drucker's 1954 observation: "a company has two, and only two, functions: marketing and innovation".Here are some more insights… Share on XWhen we treat innovation as a special, or bolt-on, function we set it up to fail. I’ve been there. Knocking on the door of business as usual trying to get it open to show innovations. It rarely works. It’s like having a child constantly trying to distract an adult from serious work.

Innovation becomes disjoint to the real business. And it is seen as someone else’s problem.

No wonder PWC uncovered that 54% of organisations struggle to bridge the gap between business and innovation.

The solution is not more innovation competitions, ideation sessions, building innovation rooms or diving into open innovation. These lead to innovation theatre – innovation activities that ultimately lead to no tangible outcome.

We need to fix our enterprises to be innovation-first organisations.

We misalign the signalling of Innovation ambition, vision and strategy

How many times do we hear CEOs calling their team to find the next disruptive innovation in their market/industry? Yet find this ambition is not aligned with vision and strategy?

CEOs calling for one type of innovation – disruptive, for example – but not enabling the enterprise to deliver that is a leading cause of the innovation problem.Here are some more insights… Share on XThere are many ways to view types of innovation. To name a few:

- disruptive, radical, incremental

- product, service, business model

- from a tech push or demand-driven perspective

Not enabling the enterprise to fulfil the ambition leads to the innovation problem. Therefore our innovation events spawn exciting ideas that just “don’t align with strategy”, so will never get past the inertia of implementation.

The CEO needs to lead and set the innovation vision. And they must ensure it flows through the organisation. We can look at the implementation of innovativeness as an innovation adoption problem.

We’re using a poor definition of value…

What is your definition of value and how is it created?

I would bet it involves how much you have paid for something. And that a manufacturer/provider has created that value you are buying. Don’t worry, that’s a common view. One that is reinforced by sales and marketing courses and business schools all over the world. And it’s based on our very goods oriented view of the world. Where the key observation is of value-in-exchange.

A poor definition of value underpins the innovation problem…it's not embedded, exchanged, and destroyed. It's co-created in use. Share on XBut this way of understanding value means we miss many observations of how the world truly works. It drives us into operational excellence and price maximisation. It makes us myopic, as we’re about to see, and gives us a poorer view of what innovation should be.

We can do better and see that value is all related to how much progress someone can make with some aspect of their life with our help. And that value is co-created in use, not embedded before purchase. The world of service-dominant logic opens our eyes to an actionable methodology for innovation.

We get myopic

With a poor focus on value we risk becoming short-sighted. Our innovations become stagnant – how many more blades, for example, does a razor need? Levitt said back in 1969 “people don’t want to buy a 1/4 inch drill, they want a 1/4 inch hole”. But we tend to focus on producing “better” drills.

Being short-sighted and not able to focus on what progress a beneficiary is trying to make reduces innovation. Adding yet another blade to the razor is not the best application of innovation.Here are some more insights… Share on XChristensen et al noted:

Every marketer we know agrees with Levitt’s insight.

Yet these same people segment their markets by type of drill and by price point; they measure market share of drills, not holes; and they benchmark the features and functions of their drill, not their hole, against those of rivals.

“Marketing malpractice: the cause and cure” Christensen, Cook, and Hall (2005)

Innovation without focussing on what progress the beneficiary is trying to make is not a route to success.

…And therefore we have a poor view of innovation.

Having a less useful definition of value and getting myopic means we struggle to understand what successful innovation is. In fact, we typically start defining innovation around the theme of “implementing something new that adds value”. And we then interpret that as something a manufacturer makes that has embedded value. Where a customer is prepared to pay the maximum the manufacturer can get so that they now own that value.

The innovation problem: our typical definition of innovation makes us focus on manufacturers; not the beneficiary.Here are some more insights… Share on XBut we need to see value differently – as the amount of progress a beneficiary makes. And then see an enterprise as one of many options the beneficiary can choose to help them make that promise. The enterprise offers a value proposition.

Innovation naturally evolves as the act of creating a new proposition that helps the beneficiary make progress better than they currently can.

Ideas-first is a tough way to innovate

Innovation can be ideas-first driven – having ideas and then trying to find the real problem that idea fits. It is a tempting approach, driven by people convinced they have a great idea.

The innovation problem: Ideas-first is not the way to innovate, yet many innovation approaches take this way.Here are some more insights… Share on XAlthough I will not go as far as Ulwick in his book “Jobs to be done: from theory to practice“, I sympathise with his view that:

the “ideas-first” approach is inherently flawed and will never be the most effective approach to innovation. It will always be a guessing game that is based on hope and luck, and it will remain unpredictable.

Ulwick (2016) “Jobs to be done: from theory to practice“

In a sense, there is a pyramid of ideas/innovations as I show in Figure 6.

Firstly, how many ideas can become innovations? And then, which innovations can the organisation implement (physically, culturally, technically)? Thirdly, how many of those implementable innovations are value-generating/creating innovations (for the customer, the organisation, and anyone else involved)? And finally, how many of those potentially value-generating/creating innovations are the customers going to use and realise the value?

You may strike lucky. Doesn’t it make more sense to focus at the top of the triangle? Although Ulwick claims innovators can reach an 86% success rate through using his rather sizeable 84-step implementation of jobs to be done theory. That figure he compares to a figure of 17% from a typical innovation process.

We don’t help ideators

Well, we think we do. We all like an ideation process. Particularly if that’s in a tool. Where people can throw ideas in, and others can comment. We get a nice panel of judges to select ideas to get funding to go a little further. Maybe a senior executive provides some coaching. But a lot of the time we’ve all had some fun but the ideas don’t really go anywhere.

Being unable to bridge the language and concept gap between ideators and sponsors contributes to the innovation problem…we can fix it by iterating over the lean business canvas Share on XA key challenge is that ideators rarely have the language and knowledge to make an idea a viable business. And similarly, executives rarely put the time in (or have the time) to coach sufficiently. Sometimes they are afraid to kill ideas early as that might break the cosy innovation culture.

We need a way of helping ideators turn ideas into something the business can really understand, challenge and improve. But without intimidating them. And we need a simple way for business sponsors to understand ideas and opportunities.

We have the Lean Business Canvas. And I believe – and have seen – it used in an iterative manner to bridge this gap.

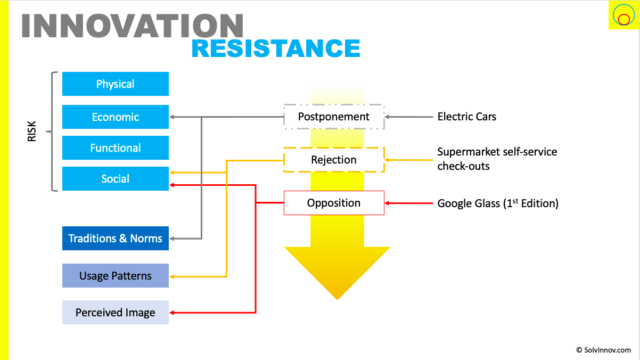

We don’t address innovation resistance

Most of us are familiar with the concepts of innovation diffusion and adoption. Where we see innovation as good and the challenge is just to get others to be aware and start using it.

However, there is a third aspect. That of innovation resistance. Where consumers might postpone, reject or oppose (actively demonstrate against) adoption.

And we rarely take this resistance into account. Yet it is usually one of the most significant risks to innovation (Heidenreich & Kraemer, 2015). Just remember the original version of Google Glass.

Wrapping Up

So, there we have my view of the innovation problem. I find it amazing that back in 1954 Drucker was defining that a firm had only two functions and over of those was innovation, yet in 2019 we are still struggling to get innovation to perform.

The rest of this site will capture my ongoing journey to fix this innovation problem. Right now, I believe the key is in getting us to think in a more service-dominant way (given that our economies are shifting that way, if not over 80% of the way already). Ending the innovation push approach we tend to fall in (separate innovation team with weak links to the business).

We’ll see that Service innovation is built around co-value generation … so please read the articles but most of all, get involved with the discussion – this way I can improve the thinking and we all can access those improvements!

There is currently one thought on “We have an innovation problem…”